Some stories defy comprehension — not just because of their brutality, but because of the tangled histories behind them. The case of Cary Stayner is one such story. Long before he became known as the Yosemite Killer, his family had already endured unimaginable trauma. His younger brother, Steven Stayner, was abducted as a child and miraculously returned home years later, a tale that captured national attention and inspired books, films, and headlines. But years later, it was Cary who would draw the nation’s gaze — this time for the brutal murders of four women in the shadow of Yosemite National Park, a place synonymous with natural beauty and quiet retreat that became the backdrop for unimaginable horror.

⚠️ This article contains descriptions of violent or distressing events. Reader discretion is advised.

The Beginning

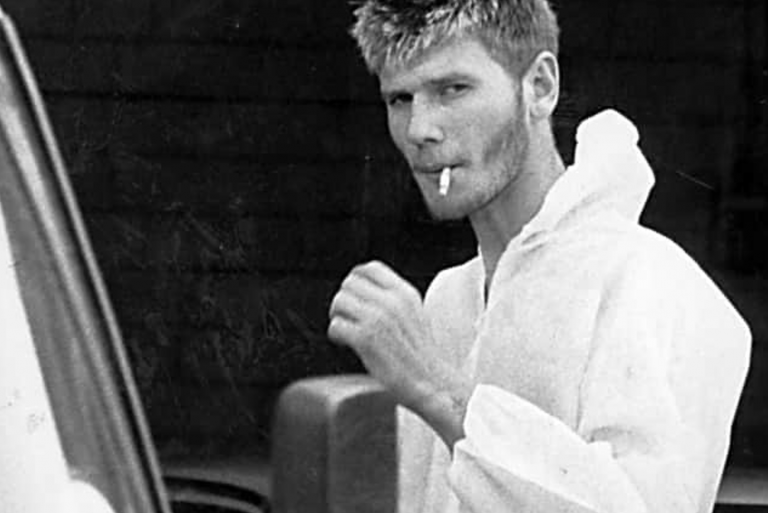

Cary Stayner was born on August 12th, 1961 in Merced, California, a small rural community about sixty miles west of Yosemite National Park. The eldest of five siblings, Cary had a brother named Steven and three sisters: Cindy, Jody, and Cory. His mother, Kay, worked in daycare, while his father, Delbert, was a cannery mechanic.

The family often visited Yosemite National Park, spending time together camping and fishing. Cary, in particular, loved the outdoors and the quiet of nature, and as he grew older, he returned frequently to the park to enjoy its solitude.

A defining moment for Cary and his entire family came when his younger brother Steven was kidnapped at the age of 7 by a paedophile named Kenneth Parnell. (Read about Steven’s case here.) Cary was 11 when Steven disappeared, and he had to navigate not only his own trauma but also the pain of watching his family fall apart. It was the first time Cary saw his father cry.

Much of his parents’ attention was consumed by the search for Steven, and Cary spent years feeling neglected. Delbert would later testify that the children were overlooked after Steven went missing, and he would frequently yell at Cary. Kay, on the other hand, was emotionally distant. As a child, she had attended a Catholic boarding school where she suffered physical and emotional abuse — experiences that later affected her ability to show affection to her own children. One of Cary’s sisters would later testify that the children tried to stay quiet and avoid upsetting their parents.

Years later, Cary told Mike Echols, author of the book, I Know My First Name is Steven, that every night for the seven years Steven was missing, he would wish on a star for his brother’s return.

As Cary grew older, he developed into a talented cartoonist. In the seventh grade, he was placed in the Gifted and Talented Education (GATE) programme, and he went on to draw cartoons for his high school newspaper, The Statesman. At 18, his classmates voted him the most creative student in his graduating class.

Many expected Cary to pursue a career in art, but none of the jobs he held were related to his creative talents. Instead, he worked a series of menial roles, including stints at a furniture removal company and an aluminium firm. Most of his working life was spent as a glass installer, repairing and fitting windows for various companies.

Cary struggled with relationships throughout his life. In high school, he was described as a quiet loner, and none of his peers recalled him ever dating.

His relationship with women was far from typical. Cary claimed to have had his first violent fantasy at the age of 7, when he would gaze through the grocery store window and fantasise about catching and killing the female cashiers. As he entered his teenage years, these thoughts grew darker and more sadistic, and he imagined women marching naked and being gang raped.

When Cary was about 12, he and a group of neighbourhood boys stripped and ran back and forth several times in front of two girls sitting on the back of a flatbed truck near the Stayner home. In later interviews, Cary’s cousin recounted how he would pretend to hypnotise her and his sisters, then try to persuade the girls to undress.

At 16, Cary’s sister hosted a sleepover, and their neighbour, 14-year-old Flores Tatum, stayed the night. During the evening, Cary crept beneath the cot she was sleeping on and touched her breast. She told him to leave, which he did — only to return later, standing naked in the doorway and exposing himself to her.

Years later, when Cary needed a place to stay, he moved in with his younger sister, Cory. His cousin later claimed that Cory discovered a video camera hidden in the bathroom, which Cary had placed there to film her showering.

In a confession Cary made years later to the FBI, he revealed that at the age of 11 — the same year his brother Steven disappeared — he was sexually molested by a paternal uncle. Most sources name the uncle as Jesse ‘Jerry’ Stayner, though there is reason to believe Cary may have been referring to a different uncle. Cary described how his uncle showed him child pornography, and he became fixated on some of the images he saw.

Cary’s accusation against his uncle adds another layer of complexity to his already troubled relationship with sex — a struggle that only worsened as he battled impotence throughout his adult life.

In 1980, when Cary’s brother Steven returned home and the family was reunited, the local media descended on the Stayner household. Once again, the now 18-year-old Cary felt pushed aside. He may have spent years wishing on a star for his brother’s return, but now he was consumed by jealousy as he watched the outpouring of attention Steven received.

Steven, meanwhile, was struggling to adapt to life back home. He was no longer the 7-year-old boy his family had last seen, but a traumatised teenager who had spent seven years living with a paedophile. As the family rallied around him, Cary resented the attention Steven continued to receive, as well as the leniency shown to him in light of what he’d endured.

Feeling overlooked once more, Cary would retreat to Yosemite to seek solace in nature, smoke weed, and sunbathe naked.

Then, on September 16th, 1989, Steven Stayner was killed in a hit-and-run motorcycle crash at the age of 24, leaving the family devastated.

Just over a year later, tragedy struck again. In December 1990, Jesse Stayner had returned home from work to find an intruder inside his house at 1321 Brantley Street, Merced. The man confronted Jesse and shot him with his own gun before fleeing with the weapon and Jesse’s truck, leaving him to bleed to death. A passing neighbour noticed the open door and discovered Jesse’s lifeless body crumpled in a bloody heap on the floor.

At the time of Jesse’s murder, Cary had been living with his uncle and claimed he was at work when the shooting occurred. He told police he’d seen a drifter loitering near the house beforehand, though the man was never found. Cary wasn’t initially considered a suspect, and Jesse’s murder remains unsolved.

In 1991, shortly after losing his uncle and his brother, the now 30-year-old Cary attempted suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning.

Poor mental health had plagued Cary since childhood. At the age of 3, he was diagnosed with trichotillomania, a compulsive hair-pulling disorder that led to relentless bullying at school. He often wore hats to hide the bald patches on his scalp.

By 1995, Cary was working at Merced Glass and Mirror when his friend, Michael Marchese, found him outside the workplace, shaking, incoherent, and pounding his fist against a sheet of plywood. Apparently in the midst of a mental breakdown, Cary told Michael he wanted to drive his truck into the office, kill his boss and everyone inside, and then set the building on fire.

Marchese alerted their boss, who drove Cary to a psychiatric centre in Merced. Though Cary received treatment, he refused to attend group counselling and soon discharged himself. He returned to the glass company only to collect his final paycheque, telling colleagues he was heading to Santa Cruz to study cartooning. But that was a lie.

Instead, Cary made his way to El Portal in Mariposa County to live and work near Yosemite National Park — where years of anger, resentment, and sexual frustration would begin to boil over, unleashing the monster he was soon to become.

Yosemite

In the summer of 1997, Cary was hired as a handyman at the Cedar Lodge Motel in El Portal, Mariposa County, just eight miles from Yosemite National Park. The work was seasonal, but he was allowed to keep his accommodation above the motel restaurant, even when he wasn’t working.

On his days off, Cary would drive to a secluded spot by the Merced River and walk down a steep bank to a beach of boulders and sand. There, he’d strip off his clothes and light a joint. Yosemite held fond memories from his childhood — but something else drew him to the area. Cary was adamant that, as a boy, he’d seen Bigfoot. He would tell anyone who’d listen about his encounter, and for years, he searched Yosemite hoping to relive the experience.

During the two years Cary worked at the Cedar Lodge Motel, he presented himself as a friendly, reliable employee, always ready to lend a hand. Colleagues saw him as a positive figure. But beneath the surface, Cary was exhibiting predatory behaviour. He tried to pick up teenage girls around the lodge, and at night, he’d take the high school girls working at Mountain Pizza to a gazebo to get high.

Cary befriended 17-year-old Jen Yates, whose family ran the bar and restaurant at the lodge. The two would go for long walks in the woods or sit by the river.

But Jen’s mother, Trisha, was disturbed that a man in his thirties was flirting with teenage girls and found his behaviour creepy. Jen thought her mother was overreacting — until one night in the summer of 1997 when Cary invited her up to his room. Minutes later, she returned to the bar, shaken, telling her mum that Cary had been pulling his hair out and ranting about his “bitchy sisters.” Trisha told Cary to stay away from her daughter.

In the summer of 1998, Cary began stalking two preteen girls from Finland who were staying at the lodge. One night, he used the motel’s master key to try to enter their room while they slept. He was armed with a metal pipe and duct tape. Fortunately, the key didn’t work, and the girls’ guardian woke when she heard Cary fiddling with the lock. She shouted out, and Cary fled.

Around this time, Cary began a relationship with a waitress at the lodge. Her daughter, Lenna, was just 10 years old when Cary entered their lives. Lenna recalled the early days fondly. Cary gave her and her sister new Beanie Babies each time he saw them, brought them drawings he’d made, and taught them how to dive. But years later, Lenna was horrified to learn from the authorities that Cary had planned to rape her and her sister, and had made three separate attempts to murder them and their mother.

The first attempt came when Cary visited their home to fix an electrical issue. His plan was to rape the girls, murder the family, and burn the house down — but he couldn’t find the property. After that night, Cary realised he hadn’t been properly prepared as he didn’t have a weapon. From that moment on, he assembled a murder kit and carried it with him at all times.

Cary made another attempt on February 15th, 1999. He drove to the family’s property to carry out repairs, this time fully equipped. But a male was present on the grounds, and Cary’s plan was thwarted. Frustrated, he returned to the lodge. He tried to use the pool, but it was dirty, so he obtained the master key from the main office to clean it. Once finished, he pretended to drop the key into the drawer, but instead walked the grounds with it, a frustrated man.

Cary passed a room where four young girls were staying. He’d seen them the day before with a man and wasn’t sure if they were now alone, so he backed off.

That night, Lenna, her family, and the four girls had a lucky escape. But three other women who had arrived at the lodge the previous day would not be so fortunate. When Cary passed the window of 42-year-old Carol Sund, her 15-year-old daughter Juli Sund, and Juli’s 16-year-old friend Silvina Pelosso, the monster inside him was at boiling point — and ready to be unleashed.

The Yosemite Monster

Carole and Jens Sund lived in Eureka, California, with their four children. High school sweethearts, they had been married for twenty-one years. Their 15-year-old daughter, Juliana (Juli for short), was born in 1983. Shortly after Juli’s birth, the couple adopted Jonah. When Jonah’s birth mother had another child a year later, Carole and Jens adopted his sister, Gina. Finally, they adopted Jimmy.

Carole came from the wealthy Carrington family, which had made millions in Northern California real estate. She and Jens were successful realtors and owned several malls across the country. Yet despite her privilege, Carole used her wealth to help others. She volunteered to support couples hoping to foster or adopt children, and she joined the board of Court-Appointed Special Advocates to help oversee the treatment of abused and neglected children in the legal system. She was also an advocate for ‘Tony V’, a child who had been locked in a cage by his family in Eureka — a case that made headlines nationwide.

Alongside her mother, Carole founded Butler Valley Inc., a non-profit organisation that runs two homes for people with developmental disabilities. Carole’s older sister lived in one of the homes.

Juli Sund shared her mother’s caring nature. When two cheerleaders from her high school were raped at knifepoint by a 21-year-old unemployed man, Juli joined an anti-rape campaign to raise awareness about sexual violence.

Her friends described her as happy and full of energy. Juli had taken up cheerleading — not because she was a girly girl, but because she loved the competition. She dreamed of becoming an architect, and her interests included writing, poetry, and playing the piano and violin.

In February 1999, Juli’s 16-year-old friend, Silvina Pelosso, a foreign exchange student from Argentina, stayed with the Sunds. Silvina’s mother, Raquel, and Juli’s mother, Carole, had met over twenty years previously when they were themselves high school exchange students. Carole had stayed with Raquel for six months on her family’s cattle ranch. The two girls struck up a friendship and exchanged friendship rings. They kept in contact throughout the years, and now their daughters were following in their footsteps.

The Sunds entertained Silvina for several weeks by taking her around well-known places in America such as the Bay Area and Disneyland, and they were now embarking on another trip.

On February 12th, 1999, Carole, Juli, and Silvina left the family home and headed for Yosemite National Park. Yosemite held special meaning for Carole and Jens as it was where they had honeymooned. Jens, however, would not be joining them on this trip. Instead, he planned to meet them later at San Francisco airport. From there, Carole and Juli would return home to Eureka, while Jens and Silvina would fly to Phoenix, Arizona, to reunite with the other three children, who were staying with relatives. Jens had arranged a family trip to the Grand Canyon.

The journey began with a flight to San Francisco, where Carole rented a red 1999 Pontiac Grand Prix. They made a stop in Stockton so Juli could participate in a cheerleading contest at the University of the Pacific. Carole and Juli were impressed by the campus and arranged to meet another mother for a tour in a few days, when they would be passing through again on their way back to the airport.

On the 14th, they reached Yosemite’s western slope and checked in at the Cedar Lodge Motel. It was Valentine’s Day and President’s Day weekend, so the motel was fully booked. They were assigned room 509 — a unit so far from the main office that, in poor weather, guests would need to drive just to access the lodge’s amenities.

February 15th was spent exploring the park. Carole and the girls went ice skating, hiking, and marvelled at the natural beauty around them. They visited Yosemite Falls and admired the towering sequoias in Tuolumne Grove. That evening, around 6:30 pm, they dined at the Cedar Lodge restaurant. An hour later, they stopped by the service desk and rented a couple of videos to watch in their room.

By then, most of the guests who had been staying at the lodge had checked out. Room 509 was now the only occupied unit in its building, leaving Carole and the girls extremely isolated.

Around 11 pm, they were winding down for the night. They had taken some final photographs of each other, laughing and messing about in the room. Carole settled in with a book, while Juli and Silvina watched Jerry Maguire, one of the films they had rented.

Then came a knock at the door.

Carole hesitated. It was late, and she couldn’t imagine why anyone would be calling at this hour.

Standing outside the door was the motel’s handyman, Cary Stayner. He had noticed the red Pontiac sitting alone in the car park and had peered through the window of room 509 to see who was inside. When he saw Carole and the girls, and realised there was no man with them, and grew interested.

Carole opened the window to speak to Cary. She wasn’t about to open her door to a stranger at that hour. Cary claimed he had a work order to fix a leak in the piping above their room and wanted to check for water damage. Carole was understandably cautious, but Cary pressed the issue, insisting it was an emergency and urging her to let him in.

Although Cary had a master key that could open every room in the lodge, he chose not to use it. He didn’t want to narrow down the suspect list for what he was about to do. Instead, he staged an elaborate ruse: knocking loudly on other doors around room 509 and entering them long enough as though inspecting for leaks. He hoped that by the time he got to room 509, his story would seem credible enough to gain entry.

Carole remained wary, but when Cary offered to call the manager, she finally relented and opened the door.

Cary entered with his tools and a backpack. Inside the backpack was his kill kit: a gun, rope, a large kitchen knife, and duct tape. He went into the bathroom and pretended to inspect for a leak, climbing onto the toilet and pulling down the fan. After a few minutes of feigned inspection, he replaced the fan and returned to the bedroom — this time pointing a .22-calibre pistol at Carole and the girls.

He told them he was desperate for money and would leave if they cooperated. Believing his lie, they allowed themselves to be tied up. Cary ordered them to lie face down on the beds, then bound their arms behind their backs, gagged them, and sealed their mouths with duct tape. He then led Juli and Silvina into the bathroom and closed the door behind them.

Cary was now alone with Carole in the bedroom. He tied her hands to her feet with rope, knelt on her back, and used more rope to begin strangling her. It took him five minutes to kill her, later telling the FBI he hadn’t realised how difficult it was to strangle someone. He also confessed to feeling very little emotion, describing Carole’s death as little more than a task to complete. Once she was dead, Cary carried her body outside and placed it in the trunk of her rental car.

Returning to the bathroom, Cary led the terrified girls back to the bedroom, lying that Carole was in the next room. They had no idea that Cary had just murdered her. He then cut off their clothes with a knife and, at gunpoint, forced them to perform sex acts on each other. However, Silvina was menstruating, which repulsed Cary, and when she began sobbing uncontrollably, his frustration boiled over. He dragged her back into the bathroom, shoved her into the bath, and strangled her with the rope. Yet Silvina did not die easily. Cary realised she was still clinging to life, so he sealed her mouth and nose with duct tape and watched her suffocate to death.

Turning his attention back to Juli, Cary sexually assaulted her repeatedly. He forced her to perform oral sex, but Cary was frustrated as he fought against his impotence. When Juli asked to use the bathroom, Cary did not want her to see Silvina dead in the bath, so he took her to an empty room instead, where he made her shave her pubic hair before assaulting her again. Cary then left Juli tied up while he returned to room 509 to retrieve Silvina’s body, placing it in the trunk beside Carole.

Next, Cary set about cleaning the crime scene. He left damp towels on the floor to suggest a hasty departure, loaded the victims’ belongings into the backseat, and left their room keys and the video they’d been watching on the dresser. Worried his hair might be on the bedsheets, he shaved off all his body hair, ensuring there would be nothing to match if forensic evidence was collected.

At around 5 am on February 16th, Cary returned to Juli, wrapped her naked body in a pink motel blanket, and tied her into the front passenger seat of Carole’s rental car. She had no idea her mother and friend lay dead in the trunk. As Cary drove away from the Cedar Lodge, he had no plan on where to go next, and aimlessly kept driving, putting distance between himself and the motel. Despite her terror, Juli remained calm, engaging in conversation as Cary questioned her. But unbeknownst to him, she lied about everything. She wanted to keep as much composure, dignity, and privacy as she could, and even told him her name was Sarah.

Over sixty miles from the motel, Cary turned off at Lake Don Pedro. Dawn was breaking as he carried Juli down a dirt path to a secluded clearing overlooking the water — later likening the act to carrying a bride over the threshold. He told her he wished he could keep her, then raped her one final time. In a cruel twist, he told her the gun he used back at the motel hadn’t been loaded, and that they could have escaped right at the start.

After fanning out her hair and telling her he loved her, he slit her throat so deeply he nearly decapitated her. As she died, Juli made a hand gesture he interpreted as a plea to end it quickly. But he turned away instead. Cary then posed her body with her legs spread apart and her arms crossed over her chest before covering her with branches and vegetation. He hurled the knife down the hillside and paused to marvel at the sun rising over the lake.

Cary returned to the car and opened the trunk. He cut off Carole’s clothes and removed the duct tape on Carole’s and Silvina’s bodies in case it had his fingerprints on. He then drove north to New Melones Lake, a reservoir on the Stanislaus River. He had planned on driving the car into the lake, but some fishermen were there, forcing him to abandon the plan. Instead, he dumped some items, including clothing, sheets, and duct tape in a dumpster before driving off again to look for an alternative place to dispose of the car with Carole’s and Silvina’s bodies.

He eventually found a remote logging road in the Stanislaus Forest off Highway 108, driving as far as he could before wiping down the car and scattering the women’s belongings around it. Then, with a pocketknife, he scratched: We have Sarah, into the bonnet.

Cary walked to Sierra Village to catch a bus, but when he realised he had not wiped down the trunk of the car, he returned to the logging road, causing him to miss the bus. After cleaning the car, he stole $200 from Carole’s wallet and hailed a cab, using the stolen cash to pay the $125 fare. Instead of returning to Cedar Lodge, he directed the driver, Jenny Paul, to Yosemite Lodge — the same hotel where Parnell had worked when his brother, Steven, was abducted. Paul later recalled Cary seemed exhausted and even pointed out a barn in Foresta, claiming he’d seen Bigfoot there in 1982. From Yosemite Lodge, Cary caught a bus back to Cedar Lodge, needing to return by 5 pm for his night shift.

Two days later, Cary revisited the rental car with a can of gasoline. He retrieved Carole’s credit card insert from her wallet, then set the vehicle alight. To mislead investigators into thinking robbery was the motive, he drove two hours west to Modesto and tossed the wallet insert from his window at an intersection.

Carole and the girls did not turn up for their campus tour at the University of the Pacific, nor did they arrive at the airport to meet Jens as scheduled. Jens’ own flight to San Francisco airport had been delayed due to bad weather, and he arrived five hours late. When they weren’t there, he assumed they’d gone on ahead and wasn’t initially concerned.

But when Jens arrived in Arizona, Silvina was not there. He called home to check whether Carole and Juli had returned safely, but there was no answer. Still, Jens remained calm, reassuring himself and others that Carole was a strong, resourceful woman and that there must be a logical explanation. He was so composed that he played a round of golf in Phoenix the following day.

As time passed with no word from his wife, Jens began to worry that Carole and the girls had been in an accident. He contacted highway patrol, but no incidents had been reported. Carole hadn’t returned the rental car or informed the company of any plans to extend the agreement.

Jens then contacted the Cedar Lodge, where staff confirmed that Carole and the girls had checked out the previous day. When room 509 was inspected, everything appeared normal. Checkout had been completed in advance, and the keys were left on the desk, as was customary. The videos they had rented were also left behind in the room. Their luggage was gone, though a few souvenirs remained — but it was assumed they had simply decided to leave early.

Finally, Jens contacted the Sheriff’s Department to report Carole, Juli, and Silvina missing.

Sund-Pelosso Investigation

The search for Carole and the girls began on Wednesday, February 17th. Local law enforcement, Yosemite Park rangers, family members, and volunteers combed the rugged terrain of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in and around Yosemite National Park by helicopter, foot, and skis, looking for any sign of the women or their red Pontiac Grand Prix.

At first, investigators focused on the possibility of an accident, or that the women may have wandered off a hiking trail and become lost in the woodland. But any hope that Carole and the girls had simply gone missing without foul play vanished on Friday 19th, when a student discovered the insert from Carole’s wallet on a street in Modesto.

The FBI quickly became involved. Sixty agents, led by James Maddock, joined the investigation, which was now headquartered in Modesto. Jens flew there immediately and was soon joined by Carole’s parents, Francis and Carole Carrington. Silvina’s mother, Raquel Pelosso, flew in from Argentina and was later joined by Silvina’s father, Jose.

That same day, a call was made to Wells Fargo Bank by a woman claiming to be Carole Sund. She requested a duplicate ATM card but was unable to provide proof of identity. Two days later, the same caller phoned again, asking for her bank balance. This time, she provided Carole’s social security number and was given the information.

The incident gave investigators reason to suspect a financial motive behind the women’s disappearance. They began working on the theory that Carole, Juli, and Silvina had been kidnapped or were victims of a carjacking. However, if Carole had been targeted for her wealth, no ransom demand was ever made.

On February 22nd, a press conference was held, and the Carringtons offered a $250,000 reward for information leading to the safe return of Carole and the girls. A few weeks later, an additional $50,000 was added to the fund for information specifically leading to the location of the car. With the possibility of an accident now ruled out, the case was being treated as a criminal investigation.

Desperate for answers, the family spent the following weeks raising awareness and appealing to the public for help. Jens appeared on television programmes including Hard Copy, Inside Edition, and America’s Most Wanted, while Carole’s parents were interviewed on Good Morning America.

The family also hired a private investigator to monitor Carole’s bank and credit card accounts. But there had been no activity since she withdrew cash from an ATM several days before her disappearance.

Meanwhile, investigators questioned family members, including Francis Carrington, who showed nothing but concern for his daughter and granddaughter and was doing everything possible to bring them home. Naturally, Jens was also questioned. He explained that it had taken him a couple of days to contact the authorities because he had been so confident in Carole’s ability to handle herself, that foul play hadn’t crossed his mind. He took a polygraph test and passed.

Employees from the Cedar Lodge Motel were also interviewed, including a handyman who had changed the locks to room 509 on the day of the women’s disappearance. He passed a polygraph test and was quickly ruled out as a suspect.

Cary Stayner was also questioned. The FBI were stunned to learn he was the brother of Steven Stayner. Given the trauma the Stayner family had already endured, Cary was dismissed almost immediately as a suspect. Although he had been arrested in 1997 for possession of marijuana and methamphetamine, no charges were filed, and authorities believed he had since cleaned up his act.

On March 14th, a Vigil of Hope was held outside the FBI headquarters in Modesto, a poignant display of solidarity for the missing women. Over a thousand supporters attended. Carole’s daughter, Gina, read a heartfelt poem for her mother:

At a time when I need my mother’s touch most,

all I see of her are pictures nailed to a post.

When it is time for bed, I rock myself to sleep.

I try to stay strong because I know that’s what you’d want your baby to be,

but, Mommy, I don’t want you to leave me.

Just four days later, on March 18th, everyone’s worst fears were realised. A local man named Jim Powers had stopped on a remote logging road in a wooded area and stumbled upon the burned-out shell of a car. The licence plate confirmed it was Carole’s rental Pontiac. The FBI was immediately notified, and Jim would later receive the $50,000 reward offered for locating the vehicle.

Agents arrived swiftly. When they opened the trunk, they discovered the charred remains of two bodies. Though unrecognisable, it was assumed they belonged to two of the missing women. But which two? Investigators were desperate to find the third. While it was likely she had met the same tragic fate, there remained a slim chance she was still alive, being held against her will, or disturbingly, that she had played a role in the crime.

The car and its contents were transported to a crime lab for further analysis. Scattered around the vehicle were several personal items, including Carole’s bag, which still contained a credit card. Inside the bag was a camera with an undeveloped roll of film. Once processed, the photographs offered a timeline of the women’s final hours. As there were no images taken after the evening of the 15th, investigators believed the murders had occurred that night.

This theory was supported by the autopsy results. Carole’s stomach contents still held remnants of the vegetarian burrito she’d eaten at the Cedar Lodge restaurant, suggesting she hadn’t eaten breakfast the following morning.

On March 21st, the families held an informal memorial service at the site where the remains had been found. Formal identification was still pending, but the next day, on March 22nd, dental records confirmed one of the bodies was Carole Sund. A week later, DNA testing identified the second body as Silvina Pelosso. Still, detectives had no leads on Juli Sund’s whereabouts — until March 25th. The day before, a letter had arrived at the Modesto Police Department. Postmarked March 16th, it had been delayed due to a postal mix-up. The sender not only confirmed the identity of the second body in the trunk but also included a hand-drawn map detailing the exact location of Juli’s remains. At the top of the note were the chilling words: We had fun with this one.

Following the map’s directions, investigators travelled over thirty miles from the site of the burned car to a clearing near Lake Pedro in Tuolumne County. More than a month after she had vanished, they found Juli Sund’s badly decomposed body leaning against a large tree. She was naked, her throat had been cut, her ankles duct-taped together, and her arms folded over her chest.

Detectives examined the note, hoping DNA from the envelope’s seal might identify the killer. But unbeknown to them, the DNA belonged to someone else. Cary Stayner had paid a stranger $5 to spit in a cup, claiming he needed to take a paternity test but didn’t want to pay for the child.

Back at the Cedar Lodge, Cary Stayner was actively assisting the FBI with their investigation. When pink fibres were discovered during the examination of Juli’s body, investigators suspected they may have come from a blanket. Cary was assigned to help by unlocking motel rooms so agents could search for the source of the fibres. He was cooperative throughout, and there was no reason for the FBI to suspect him.

His colleagues also saw no cause for concern. Cary hadn’t been working at the lodge at the time of the murders due to the seasonal nature of his job — he’d been laid off in January and only rehired on March 18th. However, he had continued living in employee housing during that period. Rather than risk drawing attention by leaving, Cary chose to stay on the property.

At night, he would sometimes sit with locals and fellow lodge employees, quietly listening as they discussed the case. He nodded along in agreement, echoing their horror at the killings. To everyone around him, he was just another concerned member of the community.

The FBI was now working on two key theories. First, the location where the car had been found suggested the crime had likely been committed by someone local. Only someone familiar with the area would know that locals often burned rubbish and old appliances there, meaning the smoke and smell of burning wouldn’t raise alarm.

Second, there was growing speculation over whether a single person could have controlled three women, prompting investigators to explore the possibility of multiple perpetrators. The note found with Juli’s body — WE had fun with this one — along with multiple crime scenes spread across several counties, further supported the theory of a group involvement.

With this in mind, the FBI narrowed its focus to known criminals within a 75-square-mile radius between Modesto and Sonoma. Many of the suspects were methamphetamine users with violent histories.

Among them was 38-year-old Billy Joe Strange, a graveyard shift janitor at the Cedar Lodge restaurant who had been working the night Carole and the girls dined there. Strange had a violent past and came under scrutiny after the husband of a lodge employee he’d been romantically involved with was found stabbed with scissors and drowned in a creek. Though ruled a suicide, the circumstances were suspicious. Strange was arrested in March for violating his parole and had no alibi for the night of the murders. A search of his home and van revealed stains that looked like blood, but tests later confirmed they were rust. During his polygraph test, Strange became aggressive, nearly attacking the examiner, and the results indicated deception.

Another suspect was 42-year-old Michael Larwick, whose criminal record included rape, kidnapping, and attempted manslaughter. In 1975, he had raped a relative while her children cowered in a nearby car. Larwick came to the FBI’s attention the day after the vigil when an officer spotted him driving with expired tags near the location where Carole’s wallet had been found. Larwick fled, leading police on a chase that ended in a crash at a convenience store. He then opened fire, injuring the officer, and a 14-hour standoff ensued before his arrest on March 16th. He denied involvement in the murders, and his polygraph results were inconclusive.

Larwick’s half-brother, 32-year-old Eugene Dykes, also became a suspect. His record included rape, kidnapping, weapons offences, and drug charges. Originally arrested on March 5th for a parole violation, Dykes drew further attention after resisting arrest and holding officers at gunpoint for two hours before surrendering. He initially denied any role in the murders but failed a polygraph test. Later, he confessed to being involved, claiming he hadn’t committed the murders but had disposed of the victims’ belongings. At one point, he even signed a statement saying he had cut Carole’s throat and helped burn the bodies, though this couldn’t be verified due to how severely burned Carole’s body was. Dykes changed his story multiple times, and investigators struggled to corroborate his claims. Acrylic fibres analysed at the FBI lab in Washington linked both Dykes and Larwick to the case, but Dykes was ruled out as the letter’s author because he was already in custody when it was sent.

The FBI continued to investigate other suspects believed to be connected to the case. These included Strange’s roommate, Darrell Gray Stephens (55), who was jailed on March 14th for failing to register as a sex offender after a previous conviction for rape. Larry Duane Utley (41), an associate of Larwick and Dykes who was arrested in May on an unrelated charge but later released. Kenneth Stewart (24), a former cellmate of Dykes who was charged with attempted murder. Angelia Dale who was subpoenaed because she is a friend of both Dykes and Larwick. Maria Ledbetter (24), a methamphetamine addict and former girlfriend of Dykes. Jeffrey Wayne Keeney (32), who was arrested on an unrelated drug charge. Teresa Kay Gray (36), who had a warrant out for her arrest after she failed to appear in Stanislaus County Drug Court in June. And Rachel Lou Campbell (36), found in possession of Carole Sund’s bank account and ATM details. She was charged in April with stealing cheques and credit cards, converting them into cash and merchandise worth $365,000.

By mid-April, those detained were ordered to testify before a grand jury in Fresno, California. With many suspects turning on each other, FBI agent James Maddock was confident the killer was already behind bars. By the end of June, he issued a public statement declaring that the key players had been arrested and were in jail on unrelated charges.

The public breathed a collective sigh of relief. Convinced the nightmare was over, people stopped reporting suspicious activity. Even Jenny Paul, the cab driver who had picked up Cary after he murdered Juli, considered contacting the FBI about her unsettling passenger, but after hearing Maddock’s statement, she decided it wasn’t necessary.

But the FBI had made a grave mistake. With the public’s guard down and investigators chasing the wrong leads, Cary Stayner was free to kill again.

Joie Ruth Armstrong

Joie Ruth Armstrong was a 26-year-old naturalist working at Yosemite National Park. Bubbly and enthusiastic, she was an educator with the Yosemite Institute — a non-profit organisation that partnered with the National Park Service to run environmental education programmes. Joie was passionate about connecting children to nature and teaching them to protect and appreciate the natural world. She loved her work, and she was good at it.

Joie rented a green, wood-framed cabin known as The Green House in the Meadow, located in Foresta — part of an enclave of around thirty cabins used by Yosemite Park staff. She lived there with her fiancé and another roommate. Like most people in the area, Joie was aware of the murders of Carole, Juli, and Silvina, but she believed the FBI’s assurances that the killer — or killers — were in custody. She even wrote in her diary: The monsters are gone.

So, on July 20th, 1999, when her boyfriend and roommate were away for the night, Joie didn’t feel overly concerned about being left alone. Besides, she was planning to visit a friend in Sausalito, California, the next day, so she’d only be alone for one night.

Early the next morning, Joie was packing her car for the trip, unaware that someone was watching her. Cary Stayner approached and began talking about his Bigfoot encounter, claiming to have seen the creature near a barn close to Joie’s cabin. Joie was naturally cautious, but she listened politely.

Cary continued the conversation, gradually gaining her trust. Once he was certain she was alone, he pulled out a gun and ordered her back inside the cabin. He bound and gagged her with duct tape. To keep her compliant, Cary used the same tactic he had with Carole and the girls, telling Joie he only wanted money and would leave if she cooperated.

But Joie soon realised Cary had no intention of simply robbing her.

He forced her into his baby-blue 1979 International Scout and began driving. But he didn’t get far. Joie, with her hands still tied behind her back, launched herself headfirst out of the open window of the moving vehicle. She managed to get to her feet and began running for her life.

Cary abandoned the truck in the middle of the road and gave chase. He quickly caught up to Joie and knocked her to the ground. The two struggled, and Cary pulled out a knife, slashing Joie’s throat. But Joie was a fighter. She resisted fiercely, pressing her chin to her chest to shield her neck from further cuts. Cary, however, was too strong. He struck again, this time delivering a fatal wound.

Once Joie was dead, Cary dragged her lifeless body down to a creek. He returned to his vehicle, parked it, then came back to where Joie lay. Placing his foot on her head, he hacked at her neck and decapitating her. He concealed her headless body under leaves and reeds, then threw her head into the creek’s drainage ditch.

Joie’s incredible fight for survival had left behind a trail of evidence he couldn’t clean up. Unlike the murders of Carole, Juli, and Silvina, this scene was chaotic. The struggle, the abandoned vehicle, and Joie’s desperate escape attempt all pointed to something horrific.

But Cary drove away anyway, leaving the evidence behind. He didn’t get far. His ageing baby-blue 1979 International Scout broke down not long after. Stranded, Cary flagged down a passing park ranger and asked for a lift. The ranger later reported that Cary seemed perfectly calm. He certainly didn’t act like a man who had just decapitated a young woman.

Armstrong Investigation

When Joie didn’t arrive in Sausalito as planned, her friend contacted the police. A park ranger went to the Green House and found the cabin door open, with music still playing on the stereo. Joie’s truck, packed with her belongings, was parked outside. It was clear she hadn’t left as intended.

More rangers arrived and began searching the area. A broken pair of sunglasses and a red mechanic’s hat were found on the ground, along with tyre tracks from another vehicle.

Later that day, Joie’s headless body was discovered partially submerged in a creek near the cabin. Her pants were undone, and her legs were placed in a sexual position. Her bra had been pushed up over one breast. It wasn’t until the following day that her head was found under the water, about forty feet away.

Doug Ramsey, the park ranger who had given Cary a lift after his truck broke down, and Jeff Powers, an employee of the Yosemite National Park Fire Department, both came forward to say they had seen Cary’s vehicle near the cabin on the night Joie was killed. On July 22nd, a BOLO was issued. Soon after, a vehicle matching the description was spotted parked off Highway 140 near a popular skinny-dipping spot along the Merced River.

Two rangers and a Mariposa detective were sent to investigate. They found Cary sunbathing nude and smoking marijuana. Cary told the officers he was the handyman at the Cedar Lodge and confirmed the vehicle was his. He agreed to let them search the truck, but refused to let them look inside his rucksack. At that point, Joie’s head hadn’t yet been found, and officers suspected Cary might be hiding it. They seized the bag and waited for a warrant.

That evening, Cary was picked up and interrogated. He denied any involvement in Joie’s murder and claimed he hadn’t been in Foresta. He was released but told not to leave El Portal.

Meanwhile, investigators compared the tyre tracks on Cary’s vehicle to those left at the scene of the crime. They were later confirmed to be an exact match. Cary’s backpack was searched and found to contain a knife, a camera, a beer bottle, a harmonica, and tanning lotion. It also held a copy of the novel Black Lightning by John Saul, about a sadistic serial killer who cuts women open while they’re still alive. The most incriminating item, though, was a packet of sunflower seeds — its torn wrapper would later match a piece of plastic found in Joie’s cabin.

With the evidence stacking up against Cary, authorities returned to his apartment the next day, but he was gone. He had sold his possessions to employees at the lodge, claiming he needed money to fix his truck. In reality, he had fled to a nudist resort in Wilton called Laguna del Sol.

However, before arriving at the resort, Cary made another attempt to find Lenna and her sister — his third attempt at raping and killing them. Fortunately, his plan failed again, as another man was staying at the house.

Cary wasn’t at Laguna del Sol for long before a fellow guest, who had seen news reports about him, alerted the authorities. On July 24th, agents John Boles, Ken Hittmeier, and Jeff Rinek were assigned to collect Cary from the resort and transport him to the FBI office in Sacramento. At this stage, the agents believed Cary was only a witness in the case and had no idea he was involved in Joie’s murder. So when they approached Cary at breakfast, they found it strange when he stood up and placed his hands on his head.

The agents didn’t arrest Carey. During the drive back to the office, Rinek chatted casually with Cary. He asked about Cary’s brother, Steven, and Cary responded, saying he thought Parnell got off easy.

Back at the FBI office, Cary was given a short biographical background interview and then offered the choice of either eating pizza next or taking a polygraph. Cary said he wanted to skip the polygraph and speak to Rinek alone. Rinek had made Cary feel so at ease in the car that Cary now trusted him, and his life story tumbled out.

Cary told Rinek about his thoughts of harming girls. He spoke about his erectile dysfunction, his obsessive hair-pulling, and how he had been molested by his uncle when he was 11. But the most shocking moment for Rinek — who still believed Cary was just a witness — was when Cary admitted to killing Juli, and said he had information about the murders of Carole and the girls.

In exchange for this information, Cary made a disturbing demand. He asked for child pornography, telling the agents, “I can’t go to prison for the rest of my life and be happy without seeing it.”

The FBI knew the request would never be granted, but they needed Cary to keep talking. To buy time and regroup, agents Boles and Rinek gave Cary pizza. As the three men sat eating lunch, Cary confirmed his guilt by saying the pizza would be his last as a free man.

But Cary had more demands. He wanted his parents to receive the $250,000 reward money in exchange for his cooperation, and he asked to be sent to a prison near his parents’ home in Merced.

Neither request was within the FBI’s control. Still, Rinek persuaded Cary to continue talking. Cary went on to reveal details only the killer would know. He said he made Juli shave her pubic hair. He admitted to sending the letter and map, and described facts that hadn’t been released to the public. He then gave a full confession, detailing what he had done to Carole, Juli, and Silvina.

Cary was arrested and jailed for the night.

The next day, the FBI drove Cary to the crime scenes. In front of a video camera, he walked agents through the murders. In Foresta, he retrieved the knife he had dumped in the woods after killing Joie. His fingerprints were on the handle. At Don Pedro Lake, Cary showed them where he’d thrown the knife used to kill Juli. The FBI recovered it, along with the duct tape used to bind her. Cary also led them to a cliff on the way to the lake and pointed out where he had thrown the pink blanket he’d wrapped around Juli.

There was no doubt the FBI had their man.

James Maddock held a press conference later that day. With the Carringtons by his side, Maddock announced that Cary had been arrested and that the FBI had information linking him to the Sund-Pelosso murders. He also said the FBI were working to determine whether Cary had acted alone or with others.

The next day, on July 26th, Cary appeared in federal court in Sacramento and was charged with Joie’s murder. He was detained in Sacramento County Jail.

While in custody, Cary gave a jailhouse confession to Ted Rowlands, a reporter from KNTV. In the interview, Cary admitted to murdering all four women. He said he had dealt with “voices in his head” urging him to do terrible things since childhood, and that the recent murders happened because he could no longer resist. Cary also told Rowlands to contact Hollywood producers because he wanted a movie of the week made about him. He wanted a bidding war. He wanted everyone to hear his story, just as they had heard Steven’s.

Trial of Joie Armstrong

On August 5th, 1999, Cary was indicted for Joie Armstrong’s murder. He pleaded not guilty.

Because the murder had taken place inside Yosemite National Park, the case fell under federal jurisdiction, and on February 11th, 2000, federal prosecutors announced their intention to seek the death penalty. U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno approved the decision.

But the case never went to trial. In September 2000, Cary changed his plea to guilty of premeditated first-degree murder, felony first-degree murder, kidnapping resulting in death, and attempted aggravated sexual abuse resulting in death. The plea came after prosecutors struck a deal sparing him from execution.

Joie’s mother, Leslie Armstrong, agreed to the bargain. She knew the death penalty wouldn’t bring her daughter back and wanted to avoid the agony of appeals.

For Joie’s murder, Cary was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Trials of Carole Sund, Juli Sund, & Silvina Pelosso

On October 20th, 1999, Cary was officially charged with the murders of Carole Sund, Juli Sund, and Silvina Pelosso. Investigators had waited before charging Cary to ensure he had acted alone and didn’t have accomplices. In addition to the murder charges, Cary was also charged with burglary, robbery, forcible oral copulation, and attempted rape. He pleaded not guilty.

On June 13th, 2001, a preliminary hearing was held at the Mariposa County Courthouse. The court listened to Cary’s entire six-hour confession. As the tape played, Cary covered his ears with his hands and wept. Silvina’s father, unable to bear the detailed description of how Cary brutalised his daughter, jumped to his feet and lunged at Cary, screaming, “Son of a bitch!” Jose Pelosso was quickly restrained by officers and escorted out of the courtroom.

On January 22nd, 2002, a judge ruled that the trial would be moved from Mariposa County to Santa Clara County. Cary’s defence team argued that the case was too well known, and the intense pretrial publicity made it impossible to seat an impartial jury in California. Three hundred eligible jurors were surveyed, and 96 percent of those polled in Sacramento County were familiar with the case.

On May 22nd, 2002, Cary changed his plea to innocent by reason of insanity, because he knew the state would pursue the death penalty. On July 15th, 2002, nearly three years after the murders of Carole, Juli, and Silvina, the first phase of Cary’s trial began in San Jose.

Trial: Phase One – Guilt

During opening arguments, Cary’s attorney, Marsha Morrissey, informed the court that Cary would be taking the insanity defence. His lawyers claimed the Stayner family had a history of sexual abuse and mental illness, which had manifested in Cary’s obsessive-compulsive disorder and the murders.

A psychiatric report presented by the defence revealed that although Kay Stayner had been abused by her father as a child, she allowed him to live in the family home with her children. Kay claimed to have kept him away from her daughters. However, according to court testimony, the girls were not safe because their father, Delbert, molested them.

On July 22nd, the court heard Cary’s taped confession. On July 24th, they heard Cary’s demands to the FBI for child pornography and for his parents to receive the reward money in exchange for his confession. But since Cary confessed without his demands being met, the defence’s claim that the FBI coerced him was dismissed.

Thus, the prosecution portrayed Cary as a cold-hearted killer. The question wasn’t whether Cary committed the murders — it was whether he was insane when he did.

Over the following weeks, the defence presented expert testimony to support the insanity claim. One witness was Dr Jose Arturo Silva, a psychiatrist who had spent over 21 hours interviewing Cary in jail, speaking with his parents, and reviewing his medical history and FBI interviews. His testimony was summarised by the Fresno Bee:

In the constellation of mental illness, Cary Stayner alone apparently could fill the sky. His enduring preoccupation with the creature Bigfoot. The prophecies of Nostradamus. The nightmares of disembodied heads, the lack of empathy toward others, the violent fantasies of child rape, the obsessive hair-pulling and more…a stew of disorders such as paedophilia, voyeurism, social dysfunction, violent fantasies, mild autism, and even a family tree laden with sexual abuse and mental illness.

Closing arguments presented two opposing views: the prosecution described Cary as a sexual predator and cold-blooded murderer, while the defence argued he was a mentally ill victim of child abuse who had lost control.

On August 26th, 2002, the jury took less than five hours to find Cary guilty of the murders of Carole Sund, Juli Sund, and Silvina Pelosso.

Trial: Phase Two – Sanity

The second phase of the trial focused on whether Cary was sane at the time of the murders. If found sane, the jury would decide whether he should be sentenced to death. An insanity ruling would result in commitment to a mental institution or life in prison — a sentence he was already serving for Joie Armstrong’s murder.

The defence called Dr Allison McInnes, assistant professor of psychiatry and human genetics at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Dr McInnes testified about the genetic history of Cary’s family, which included psychosis, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance abuse, paedophilia, and other mental illnesses spanning four generations. She believed Cary was legally insane when he committed the murders.

Testifying for the prosecution was Dr Park Dietz, a well-known forensic psychiatrist. Dr Dietz argued that Cary knew what he was doing was wrong. He described Cary as one of the higher-functioning criminals he had encountered, pointing to the planning, cover-up, and deception involved in the murders.

On September 16th, 2002, the jury agreed with the prosecution. It took less than four hours to determine that Cary was sane at the time of the murders.

Trial: Phase Three – Sentencing

On October 9th, 2002, after six hours of deliberation, the jury rejected the option of life in prison and the defence’s pleas for leniency based on Cary’s mental health. Instead, they recommended the death penalty for the murders of Carole, Juli, and Silvina.

After the verdict, Cary requested a new trial, arguing that none of the jurors were molestation victims. The judge denied the request, and on December 12th, 2002, Cary was sentenced to death by lethal injection.

At the time of writing, Cary Stayner remains on death row at San Quentin State Prison, over two decades after his conviction. California has not executed a prisoner since 2006, and a statewide moratorium introduced in 2019 has effectively halted all executions. While many death row inmates have since been relocated, Cary remains housed in the Adjustment Center — isolated, monitored, and still officially condemned.

Aftermath

The conviction of Cary Stayner marked the end of a trial — but pain, grief, and unanswered questions endured. In the years that followed, the case continued to stir outrage, suspicion, and sorrow. Families sought accountability. Critics questioned law enforcement’s failures. And beneath it all, a darker uncertainty lingered: had Stayner’s violence begun long before the women entered Yosemite?

FBI Criticism

The FBI came under heavy scrutiny for their handling of the case, with many believing Joie’s murder could have been prevented. Not only had the FBI been fixated on the wrong group of people, but they falsely reassured the public of their safety — including Joie Armstrong.

Some of the suspects under suspicion had passed lie detector tests and offered to provide blood samples to support their innocence. One suspect even had conclusive proof he had been working out of state at the time of the killings. Their lawyers accused the FBI of treating their clients like patsies, waiting on the sidelines for the FBI to make up their minds.

Eugene Dykes even said during a prison interview that he gave investigators so many different stories he couldn’t think of any more. “If only they listened to me from the beginning. I told them I didn’t do it.”

Cedar Lodge Criticism

In 1999, the families of Cary’s victims filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the Cedar Lodge, contending that employees were wrong to assign the women to an isolated room and failed to do a proper background check on Cary. Both families sought unspecified sums for punitive and other damages, as well as reimbursement for funeral expenses and legal fees.

Steven Fabbro, a lawyer for the family of Silvina Pelosso, said, “Hotels and motels have an obligation to provide security for their guests from either their employees or strangers.”

In August 2003, the Sund family accepted a $1 million wrongful death settlement from Cedar Lodge.

Did Cary Act Alone?

The Stayner family believed Cary did not act alone and was taking the fall for someone else. Carole Sund’s father and husband also felt the same.

Cary’s note to the FBI with the location of Juli’s body said “we” on it, which many see as proof that Cary did not act alone. They also point to the mess Cary made of Joie’s murder as evidence that he must have had help when he murdered Carole and the girls.

Many argue that Cary’s remorseful outbreaks in court prove he did not display the actions of a psychopathic murderer.

Were There More Victims?

Many question whether Carole, Juli, and Silvina were Cary’s first victims, with some pointing to his confidence in subduing three women as an indication he had done this before. After Cary’s confession, the FBI investigated him for a number of further unsolved murders. The following are some of the victims linked to Cary:

Jesse Stayner

In December 1990, Cary’s paternal uncle Jesse Stayner was shot to death by an intruder in his home. Cary was living with him at the time and claimed Jesse had molested him when he was 11. Though Cary was a suspect, no evidence linked him to the murder. The case remains unsolved.

Patricia Hicks Dahlstrom

Patricia Marie “Patty” Hicks Dahlstrom was 28 years old when she disappeared from Washington State. She had last been in contact with her family in September 1982 after relocating to Merced, California, where she joined the San Anda Apostolic Church, a religious group founded by cult leader Donald Gibson.

An investigation into the cult revealed that sexual assaults had been carried out under various religious pretences. Gibson was put on trial in September 1981 and found guilty of four sexual offences. Patty had testified against him.

After leaving the cult, she was last seen by her roommate taking public transportation to Yosemite National Park. On June 28th, 1983, a severed arm and hand were recovered from the park. By 1988, a skull was discovered near the original scene. In 2021, genetic genealogy identified the remains as belonging to Patty.

Cary Stayner was known to have been acquainted with Gibson and attended his 1981 trial. Authorities believe Cary may have killed Patty in retaliation for her testimony against Gibson, though no formal charges were brought.

Veronica Martinez

In March 1992, the body of 19-year-old Veronica Martinez, a Sacramento waitress, was found dumped in a steep ravine between Auburn and Placerville. She had been decapitated. Although a man in Veronica’s life was suspected, investigators were unable to link him to the crime.

Sharalyn Mavonne Murphy

In October 1994, the severed hands of 23-year-old Sharalyn Mavonne Murphy were found near New Melones Reservoir. Her headless torso was found off a mountain road in Calaveras County two months later. Neither her head nor the murderer has ever been found. The FBI investigated similarities between her death and that of Joie Armstrong.

Denise Smith

In December 1994, the charred body of 34-year-old Denise Smith was found in a burn barrel near Don Pedro Reservoir, close to where Juli Sund was discovered. She had been stabbed multiple times before being burned.

Michael Madden

Michael Larry “Mike” Madden disappeared on August 10th, 1996, en route to a camping trip in the Stanislaus National Forest near Sonora, California. Authorities linked Madden to Cary because he committed his crimes near Yosemite National Park, seventy-five miles east of Sonora.

Whether these cases can ever be definitively linked to Stayner remains uncertain. But each name reflects a life lost, and a case still waiting for closure.

Conclusion

Though their lives were stolen in acts of senseless violence, Carole Sund, Juli Sund, Silvina Pelosso, and Joie Armstrong left behind legacies rooted in compassion, courage, and connection.

In the wake of tragedy, Carole’s family founded the Carole Sund-Carrington Memorial Reward Foundation, dedicated to raising awareness of missing persons and supporting families in crisis. For over a decade, the foundation offered rewards for information in countless cases, becoming a lifeline for those searching for answers. When it was dissolved in 2009, its remaining assets were transferred to the Laci & Conner (Peterson) Search and Rescue Fund, ensuring its mission would continue.

Joie Armstrong’s legacy lives on through the Joie Armstrong Memorial Fund, established in 1999 to honour her passion for helping children connect with nature. In 2000, the fund launched the Armstrong Scholars program, a transformative 12-day wilderness backpacking experience in Yosemite’s High Sierra for young women aged 15 to 18. Each participant receives a $1,500 scholarship, empowering them to explore, grow, and lead — just as Joie had inspired others to do.

For more information or to donate, visit the Armstrong Scholars program page on the NatureBridge website.

These memorials are more than tributes. They are acts of resistance against forgetting, and reminders that even in the aftermath of horror, love and purpose can endure.

Sources

Books

I Know My First Name is Steven. Mike Echols. 1999. Pinnacle Press.

The Yosemite Killer: Life of Serial Killer Cary Stayner. Jack Smith. Maplewood Publishing.

In the Name of the Children: An FBI Agent’s Relentless Pursuit of the Nation’s Worst Predators. Jeffrey L. Rinek and Marilee Strong.

Court Documents

Pelosso v. Lodge. California Court of Appeal. March 16, 2006.

Newspaper Articles

The Californian. Jurors to Determine Sanity of Convicted Yosemite Killer. 12 September, 2002. Page 20. Via Newspapers.com.

The Press Democrat. Steven Stayner’s Uncle Murdered. 27 December, 1990. Page 16. Via Newspapers.com.

TV / Movies / Videos

20/20 Evil in Eden, Pt 4: Cary Stayner Takes Refuge in Yosemite. ABC News.

20/20 Evil in Eden, Pt 5: Mother, Two Teens’ 1999 Disappearance Near Yosemite Leads to Massive Search.

20/20 Evil in Eden, Pt 6: After Third Yosemite Victim is Found, Suspected Killers Are Apprehended.

20/20 Evil in Eden, Pt 7: The Yosemite Serial Killer Claims His Fourth Victim.

20/20 Evil in Eden, Pt 8: FBI Finds Cary Stayner Has Fled to a Nudist Colony.

20/20 Evil in Eden, Pt 9: Cary Stayner Confesses Killing Innocent Women.

20/20: Paradise Lost. ABC News.

20/20 Extra: How Intended Victim of 1999 Yosemite Killer Views the Tragedy Today. ABC News.

ABC News Report: Cary Stayner Confesses to Killing a Woman in Yosemite National Park. ABC News. July 26, 1999.

Captive Audience: A Real American Horror Story. First episode date: April 21, 2022 (USA). Hulu.

Websites

ABC News. Did FBI Blunder in Yosemite Murder Case? June 13, 2001.

ABC News. July 26, 1999: Cary Stayner Confesses to Killing a Woman in Yosemite National Park. January 9, 2019.

ABC News. Woman Recalls Moment Family Learned They Were Target of 1999 Yosemite Killer: ‘Our Lives Were Flipped Upside-Down’. July 19, 2019.

Crime Library. Cary Stayner and the Yosemite Murders.

Esquire. A Voice In the Dark. January 29, 2007.

Grunge. The Untold Truth of Serial Killer Cary Stayner. October 10, 2022.

Los Angeles Times. Judge Approves Change of Venue for Yosemite Triple Murder Trial. October 30, 2001.

Los Angeles Times. Jurors Asked to Look into Mind of a Killer. August 19, 2002.

Los Angeles Times. Sister Tells of Stayner’s Troubled Childhood. October 4, 2002.

Murderpedia. Cary A. Stayner.

NatureBridge: Yosemite Armstrong Scholars.

North Coast Journal. Jens Sund Speaks. July 25, 2002.

Outside. The Yosemite Horror. November 1, 1999.

Press Democrat. Lawyer: Stayner Killed Trio, but was Insane at Time. July 16. 2002.

Seriial Killer Calendar. The Stayner Family Tragedies.

SF Gate. Defense to Fight for Stayner’s Life / Lawyers Cite Report Detailing a Life of Being Abused. May 21, 2002.

SF Gate. FBI Eyes Other Unsolved Killings. July 29, 1999.

SF Gate. FBI Missed Yosemite Cab Clue. July 28, 1999.

SF Gate. Jury Recommends Death for 3 Yosemite Murders / Formal Sentencing Scheduled for December. Oct 10, 2002

SF Gate. He Dreamed of Killing. July 27, 1999.

SF Gate. Life goes on for the Sunds. April 11, 1999.

SF Gate. Overshadowed all His Life / Low-key Cary Stayner Took Back Seat to Kidnapped Brother. July 30, 1999.

SF Gate. Plea for Tips On Missing Mom, 2 Girls / FBI Calls Kidnap Possible — $250,000 Reward Offered. February 23, 1999.

SF Gate. Stayner’s Parents Fear Losing Another Son. October 4, 2002.

SF Gate. Stayner Tried Before, Expert Says / 2 Girls From Finland Stalked Earlier, Psychiatrist Says. August 1, 2002.

SF Gate. Stunning Details in Stayner’s Confession / In Taped Statement, Handyman Tells of Slaying Yosemite Tourists. June 14, 2001.

SF Gate. The Case of a Lifetime / For Cary Stayner, There Was Something About Jeff Rinek That Put Him at Ease – And Made Him Want to Talk. December 15, 2002.

SF Gate. Yosemite Killer Sentenced to Death / Terrible Details of Stayner Case Stun Even the Judge. Dec 13, 2002.

Strange Outdoors. The Yosemite National Park Sightseer Murders and the Two Faces of Evil. November 4, 2020.