When 7-year-old Steven Stayner was abducted on his way home from school, his life was stolen in an instant — but the damage went far deeper than the missing years. Held captive by a convicted child molester and forced to live under a false identity, Steven survived seven years of manipulation and abuse. And though he eventually escaped — rescuing five-year-old Timmy White in the process and becoming a national hero — the trauma never left him. This is not just a story of a boy stolen, but of a young man haunted by what it took to come home.

⚠️ This article contains descriptions of violent or distressing events. Reader discretion is advised.

Stolen Childhood

Steven Gregory Stayner was born on April 18th, 1965, in Merced, California. The middle child of five siblings, he had an older brother, Cary; an older sister, Cindy; and two younger sisters, Jody and Cory. In 1972, 7-year-old Steven lived with his parents, Kay and Delbert, in a three-bedroom suburban home on Bette Street in Merced, a small rural community about 60 miles west of Yosemite National Park. The town’s slogan, ‘Gateway to Yosemite’, reflected its proximity to the famous park.

Before moving to Bette Street, the family had lived on a 20-acre ranch in northern Merced County, complete with an almond orchard. Steven loved playing outside, running among the trees with his dog. But the physical toll of farm work led to Delbert undergoing back surgery in 1970 after slipping a disk. Then, in 1971, a dry summer and poor irrigation forced the family to sell the farm and relocate to the city.

Steven missed the freedom of ranch life. He often got into trouble for cutting through neighbours’ yards and mourned the loss of his dog, which had been given to friends in the countryside. He also struggled to adjust to his new school, Charles Wright Elementary, frequently getting into fights with classmates and longing for his old friends from kindergarten.

By the end of 1972, Steven had begun to settle into his new life. He was happier and making friends. On December 4th, he finished school at 2 pm. It was his best friend Sharon Carr’s birthday, and he planned to visit her later to give her a present. But first, he had chores to do, so despite the rain, he headed straight home. His parents had previously reprimanded him for going to friends’ houses without permission, and he didn’t want another ‘whooping’ from his father.

As Steven walked his usual route, just a few blocks from home, he was approached by 30-year-old Ervin Edward Murphy. Murphy was handing out gospel tracts and claimed to be collecting donations for the church. He asked Steven if his mother might donate items, and when Steven said she would, Murphy offered him a ride home. Steven hesitated at first, but his strong Mormon upbringing instilled trust in elders, especially those associated with the church.

Watching the interaction from his white Buick truck was 41-year-old Kenneth Parnell. Parnell wanted a young boy to raise as his own and kept religious tracts in his vehicle, which he had previously used to approach children walking home from school. This time, he had enlisted Murphy to make the initial contact, believing Murphy’s small stature and gentle demeanour would seem less threatening to a child.

As soon as Steven accepted Murphy’s offer, Parnell pulled up beside them. Murphy opened the rear door, and 7-year-old Steven climbed in willingly.

However, instead of being taken home, Steven was driven 25 miles away to Parnell’s rented, run-down cabin at Catheys Valley Cabin Resort in Mariposa County, 50 miles from Yosemite Lodge, where Parnell and Murphy worked. Along the way, Parnell stopped at a payphone and pretended to call Steven’s parents, telling the boy they had agreed to let him stay the night. When they arrived at the cabin, Steven found several toys waiting for him.

That night, Parnell made Steven shower and join him naked in the cabin’s only bed. Murphy slept on the sofa, listening to Steven’s cries from the next room. For the next seven years, this abuse would be Steven’s new normal.

The next day, Parnell and Murphy returned to work, taking Steven with them to Yosemite Lodge. After dropping Murphy off, Parnell drove Steven to a remote area and forced the terrified boy to perform oral sex on him. Steven later explained that he complied because he didn’t want to be fighting every night, so he just did what Parnell wanted him to do.

After the assault, Parnell moved Steven to his private room in the employee dormitory at Yosemite Valley Lodge. He drugged Steven with sleeping pills so he could work undisturbed as the hotel bookkeeper. For days, Steven was confined with only a bucket for a toilet. Murphy occasionally checked on him, bringing food, books, and toys. Murphy was kind to Steven and tried to comfort him. Steven liked him and called him ‘Uncle Murphy’.

On December 11th, Parnell, Murphy, and Steven returned to the Catheys Valley cabin. Parnell left Murphy in charge while he travelled to Bakersfield to visit his mother. When he returned, he told Steven he’d been in court and claimed his parents no longer wanted him, couldn’t afford to care for him, and that a judge had granted Parnell custody.

Steven was devastated, but Parnell softened the blow by bringing home a six-week-old Manchester Terrier puppy, which he gave to him. Steven adored his new companion and named her Queenie.

While he’d been away, Parnell had stopped at a service station in Merced and spotted a missing poster of Steven. He memorised the boy’s full name, date of birth, and physical description. Using this information, he renamed Steven ‘Dennis Gregory Parnell’ and ordered him to call him ‘Dad’. A couple of days later, Parnell cut Steven’s hair shorter and dyed it a darker colour, eradicating the description of Steven’s ‘light brown, shaggy, collar-length hair’ provided on the flyer.

The next day, Parnell drove Murphy back to Yosemite, quit his job, and returned to the cabin, where he molested Steven again. The abuse escalated, and 13 days after the kidnapping, Parnell sodomised Steven for the first time. When he finished, he gave the sobbing boy sleeping pills.

The following morning, Parnell traded his Buick for a Rambler, making his connection to Steven’s kidnapping even harder for the police to trace. That day, he, Steven, and Queenie left Catheys Valley, driving 200 miles to Santa Rosa. They spent weeks in run-down motels, where Steven spent his first Christmas away from his family.

The Search

Kay had been running errands the afternoon Steven was taken and arrived ten minutes late to collect him. She hoped he had gone straight home, but when she arrived at 2:20 pm, he wasn’t there. At first, neither Kay nor Delbert was overly concerned — Steven didn’t always return right away — but as time passed, their unease grew. They called Steven’s friends, and Delbert drove around the neighbourhood looking for him, but nobody had seen him. By 5 pm, they contacted the Merced Police.

That night, a search party assisted by local Boy Scouts combed gardens, sheds, wooded areas, and construction sites. Delbert scoured the streets late into the night, even searching a junkyard by torchlight.

News of Steven’s disappearance was broadcast by the local radio station, and by the following day, television and newspapers carried bulletins. A large police presence filled the streets of Merced, with officers canvassing homes and businesses within a ten-block radius.

That same night, Delbert drove to Catheys Valley to inform Kay’s father, Bob Augustine, of what had happened. Bob lived at Judy’s Trailer Park, which, unbeknownst to them, was the same park where Parnell’s cabin stood. Little did they know Steven was residing just 200 feet away from his grandfather.

Search efforts continued for several days, supported by community volunteers and members of the Mormon church. Delbert and Kay searched tirelessly and cooperated fully with the police, even undergoing polygraph tests, which confirmed their innocence.

On December 6th, they awoke to find the FBI excavating their property.

Delbert feared Steven had been murdered. He drove around the area examining mounds of dirt, suspecting they might conceal graves. He kept a sawed-off shotgun in his truck in case he encountered Steven’s abductor. Kay, however, clung to the hope that her son was alive. She made sure someone was always home in case he called, and she and her friends distributed missing posters to schools and local businesses.

Several psychics contacted the family. Though sceptical, both the Stayners and the police followed up on all leads, desperate for answers. One psychic pointed them to the trailer park cabins in Catheys Valley, but astonishingly, these were never searched. The family assumed the connection was due to Bob Augustine, who had been strangely uncooperative during questioning, though he ultimately passed a polygraph test.

Given Merced’s proximity to Yosemite National Park, the FBI requested a list of park employees. However, the list arrived three months late — and incomplete. Employees were paid fortnightly, with half paid one week and the other half the next. The list omitted those paid during the week Steven vanished, including Parnell. Without his name, the FBI couldn’t cross-reference him with their sex offender database.

Park rangers did search Yosemite, but the Curry Company — the firm responsible for hiring park staff — had a troubling reputation for employing known criminals, including sex offenders. Despite Steven and Parnell living within reach, the search was far from thorough.

Cooperation from park management was equally lacking. When FBI agents requested permission to display missing posters, the manager refused, claiming they would frighten visitors. He further insisted that Yosemite fell under federal jurisdiction and that a warrant was required.

As a result, no flyers were ever displayed.

On December 11th, the search was officially called off, devastating the Stayner family. Christmas 1972 passed with Steven’s unopened gift — a G.I. Joe action figure — still beneath the tree.

These were harrowing times. The Stayners had no idea if Steven was alive or dead. In 1973, a child’s cowboy boot was found along the bank of Bear Creek. Authorities searched for remains, but the boot did not belong to Steven.

The family endured agonising uncertainty. Kay and Delbert pleaded with news outlets for continued coverage, but they were told Steven’s case was now ‘old news’. Still, they never gave up hope.

Later that year, Delbert and Cary repainted the garage. But Delbert made sure Cary didn’t paint over the graffiti Steven had scrawled the day before he vanished: a mischievous scribble of his name that would remain on the garage wall for years to come.

Steven’s New Normal

After Christmas, Parnell found work as a bookkeeper and front desk clerk at Santa Rosa’s Holiday Inn. He hired babysitters for Steven and threatened him with placement in a children’s home if he ever revealed his true identity.

On January 2nd, 1973, Parnell enrolled Steven at Steel Lane Elementary School, listing him as Dennis Parnell. Yosemite Elementary appeared on the paperwork as his previous school, but Steel Lane failed to question the delays in obtaining records or request a birth certificate.

In fact, that same month, the Bellevue Union School District received several of Kay’s missing persons flyers, along with a letter asking them to circulate the posters among its schools, including Steel Lane. Instead, the flyers were discarded, and no connection was ever made between ‘Dennis’ and Steven.

Having only just settled into life in Merced, Steven now faced another upheaval. On February 24th, Parnell relocated them to a small trailer on the outskirts of town at Mt. Taylor Trailer Park. Yet again, Steven was made to change schools — this time to Kawana Springs Elementary — further embedding the false identity that Parnell was carefully constructing through a new trail of documentation.

In April, Steven turned 8, and Parnell’s terrifying assaults persisted. One night, when Parnell was sleeping, Steven tried to escape, but didn’t get far down the road before he found himself lost and scared and returned to the trailer before Parnell woke up.

Isolated and manipulated into believing his family had abandoned him, Steven felt trapped. He frequently searched newspapers and watched television, hoping to find signs they were still looking for him — but never found any.

Gradually, Steven began settling into his new life. The trailer was shabby, but he enjoyed playing outside with Queenie, which reminded him of ranch life. He befriended a boy named Kenny Matthias. As their friendship developed, Parnell convinced Kenny’s mother to babysit Steven.

Parnell had begun to feel untouchable. Later that year, when Steven fell ill, Parnell managed to obtain medical treatment for Steven, despite lacking legitimate paperwork. Emboldened, he even took Steven to Denny’s without attracting suspicion. Parnell was hiding Steven in plain sight.

In November 1973, Parnell rented a spacious house in Santa Rosa, which meant Steven had to change schools again, this time to Doyle Park Elementary. Although he missed Kenny, Parnell allowed sleepovers, and the boys remained close. Parnell also began a relationship with Kenny’s mother, Barbara.

By February 1974, Parnell had lost his job at the Holiday Inn and started delivering newspapers. Unable to keep up with house payments, they returned to motel accommodation in Santa Rosa, though the move allowed Steven to re-enrol at Kawana Elementary and reconnect with Kenny.

That spring, Parnell worked at the El Tropicana Motel. His relationship with Barbara deepened. Her husband, Bob, often came home drunk and violent, and Parnell became someone she turned to. Eventually, Barbara moved into their motel room, and the three shared a bed. One drunken night, Parnell and Barbara had sex in front of 9-year-old Steven and forced him to participate.

In June, Parnell returned to the Holiday Inn, and the trio moved to North Star Trailer Park. Again, they shared a single bed. Over the next eighteen months, Steven was raped eight more times. Although he didn’t like Barbara, he later said he felt relieved when she was around because her presence reduced Parnell’s assaults on him.

Parnell’s predatory urges did not end when he kidnapped Steven. In December 1974, Parnell tried to abduct another child, enlisting Steven’s help. He instructed Steven to lure boys at a Santa Rosa mall, but Steven deliberately sabotaged the plan, telling Parnell the boys refused to go with him and lying about the conversations he really had with them.

Almost six months later, in May 1975 — not having had any luck with Steven — Parnell talked Barbara into assisting him. She attempted to lure a boy from the Santa Rosa Boys’ Club, but as soon as they approached Parnell’s car, the boy got scared and fled.

Presumably to avoid detection after their failed kidnap attempts, the trio moved eighty miles north to Willits, Mendocino County. Steven changed schools again and was enrolled at Brookside Elementary. Parnell couldn’t find steady work, and within weeks, they relocated again to Harbor Trailer Park in Fort Bragg. There, with financial support from his mother, Parnell opened a Bible store. Steven had to change schools again, this time to Dana Gray Elementary, where ‘Barbara Parnell’ was listed as his mother.

One weekend, Steven was caught shoplifting. Though briefly held by the police, he remained silent about his true identity and the abuse, fearing Parnell’s retaliation and the possibility of being sent to a care home. By then, Parnell’s lies had burrowed so deep that even the prospect of having no family at all felt more terrifying than remaining with the one that hurt him.

By spring 1976, Barbara regained custody of her four youngest children, including Kenny. Parnell’s Bible store was a failure and ended up closing, and the addition of Barbara’s family strained their finances further.

Their trailer was too small for all seven of them, so Parnell bought a converted school bus, and they ended up moving to the nearby Anchor Trailer Park. It was here that Kenny told Steven that Parnell had made advances towards him, though Steven ignored Kenny’s accusation.

Soon after, financial stress ended Parnell and Barbara’s relationship, and by June, she and her children went to live with another man she had met through work. With Barbara gone, Parnell’s abuse of Steven intensified.

In July, Parnell took a bookkeeping job at Wells Dental Supply in Comptche, Mendocino County. He rented a mobile home from a colleague, and he and Steven moved again.

For Steven, Comptche was a brief reprieve. He had his own bedroom, and he loved the outdoor life Comptche provided. He made friends at Mendocino Middle School and got his first girlfriend, Lori MacDonald.

But Parnell continued to prey on young boys. Kenny later told Steven about visiting the trailer when Parnell sent Steven out. Left alone, Kenny was cornered by Parnell but escaped before anything happened. According to the book I Know My First Name is Steven by Mike Echols, Steven then confided in Kenny about the abuse. When Kenny asked Steven why he didn’t tell anyone, Steven said he didn’t want to tell on his ‘dad’.

In another incident, Barbara left Kenny and her 9-year-old son Lloyd with Parnell in the trailer. Parnell began touching Kenny, but Kenny ran off, leaving his younger brother alone with him. Allegedly, Parnell then raped Lloyd.

Parnell propositioned other boys, offering them money or cigarettes. One boy he offered money to was 10 years old — he declined Parnell’s advances.

Another time, Parnell purchased cigarettes for Steven’s friend, George. He then served Steven and George beer and got them drunk. According to a police report filed at the time by George’s mother, Parnell sodomised George.

In another incident, Parnell got Steven and a friend drunk and photographed them nude in the shower. It wasn’t the first time Parnell had taken intimate pictures of Steven.

In the spring of 1978, 13-year-old Steven had been drinking and smoking marijuana at a party when he tearfully told several friends, including George and his girlfriend Lori, his real name and that he wanted to go home. His friends dismissed his confession as drunken rambling. Parnell had everyone fooled.

A year later, in the spring of 1979, Parnell put down a deposit on a plot of land in Franklin County, Arkansas, nestled in the Ozark Mountains. He planned to build a cabin there once the sale was finalised. While they waited, he and Steven made a sudden move to a caretaker’s cabin on Mountain View Ranch in Manchester. In exchange for guarding the property — and its cannabis crops — the owners allowed them to live rent-free.

Steven was devastated. After three happy years in Comptche, surrounded by good friends and with a bedroom of his own, he now found himself in a primitive cabin with no electricity, one bedroom, and outdoor toilets and washing facilities.

Parnell found work as a night-time desk clerk at the Palace Hotel in Ukiah, 40 miles from the cabin. Steven transferred to Point Arena High, though he often missed school due to their remote location.

By now, Steven was 14 years old, and although the abuse continued, Parnell’s sexual interest in the developing teenager was waning. His desire to abduct another child hadn’t faded, however. He still hoped to take a young boy to Arkansas and often tried to involve Steven in those plans. Several times, he drove Steven to Santa Rosa and told him to approach children, just as he had done before — but Steven deliberately thwarted each attempt.

Parnell was becoming desperate, and it didn’t take long for him to manipulate someone else into helping.

Randall ‘Sean’ Poorman was a troubled teenager looking for a way out of a difficult home life. Parnell exploited that vulnerability with cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs. He also stole marijuana from the ranch and used Sean to sell it for him.

In November 1979, while Sean was staying at the cabin, Parnell told him about his desire to ‘rescue’ a boy from a bad home and offered him $50 to help. Sean agreed.

At around 8 am on the morning of February 14th, 1980, Parnell and Sean drove to the area surrounding Yokayo Elementary School in Ukiah and watched as kindergartners arrived for the school day. Parnell already had a boy in mind. He had followed him before and knew his route. But when they failed to spot him, they decided to return later.

In the meantime, they visited charity shops where Parnell bought Sean a briefcase as a reward for helping him. Sean would later use it to carry his pornography. Parnell also purchased girls’ clothing to use as a disguise, as well as a mattress and sleeping pills, just as he had once used on Steven.

At around 11 am, they returned to the school. This time, they saw the boy. Parnell drove a short distance away and parked. He and Sean were ready to act.

Timmy White

Five-year-old Timmy White was cheerful as he left school. His class had held a Valentine’s Day party, and he had dressed as a cowboy for the occasion. Holding tightly to his goody bag of Valentine cards, he began the walk to his babysitter’s house.

As he made his way down the street, Timmy passed a parked car where an older boy crouched beside one of the tyres. The boy called out, asking for help, but Timmy declined and continued walking.

Moments later, Timmy heard footsteps approaching from behind. He broke into a run, but the boy caught up to him quickly and grabbed him. Timmy clung to a nearby chain-link fence, but the boy prised his small fingers away and dragged him, kicking and screaming, back to the car.

Once inside, Timmy was thrown into the back seat, and the door slammed shut behind him. The car sped off. In terror, Timmy was forced to swallow pills before being told to lie down. He was then concealed beneath a blanket.

Bewildered and frightened, Timmy lay still. He had no idea who these men were or where they were taking him.

Borrowed Time

Back at the cabin, Parnell carried the sleepy Timmy inside. He undressed him and changed him into pyjamas bought from a charity shop, then laid him on the bed and drugged him again.

Before Sean left, Parnell handed him whisky, marijuana, and nude photographs of a classmate as payment. He also gave him pictures of the intersection where they had abducted Timmy — a souvenir of their day. Sean dropped everything into his new briefcase, pleased with his rewards. He never returned to the cabin.

Steven found out about his new ‘baby brother’ later that afternoon when Parnell collected him from school. Timmy lay sedated in the back seat. Horrified, Steven knew what awaited him. The cabin had only two beds, and Timmy would have to sleep beside Parnell.

Back in Ukiah, a search for Timmy began as soon as he failed to arrive at his babysitter’s house. Police were quickly alerted, prompting coordinated land and air searches. News channels ran updates about the missing 5-year-old, and posters were distributed across the area. Timmy’s mum and stepdad, Angela and Jim, scoured the neighbourhood — mirroring the nightmare the Stayners had endured years earlier.

Timmy spent his first week heavily sedated. At night, Parnell left for his security job in Ukiah, leaving Steven to watch over Timmy alone. During the day, Parnell took over while Steven was at school. Still, Steven was so worried about what might be happening in his absence that he began coming home during lunch breaks to check on Timmy.

There was a small block of time each day, after Steven left for school and before Parnell returned from work, when Timmy was left alone. But the cabin’s isolated location made escape nearly impossible, especially for a child disoriented by drugs and paralysed by fear. Just as Steven had once been, Timmy was too frightened to run.

Eleven days after the kidnapping, Parnell dyed Timmy’s blonde hair brown, bringing painful memories flooding back to Steven. And the more Steven looked after Timmy, the more certain he was that he could not let Timmy suffer the same fate that he had.

Determined to save Timmy, Steven hatched a plan to rescue him by hitchhiking to Ukiah, 40 miles away. Once there, he would deliver Timmy to safety and then hitchhike back to the cabin before Parnell returned from work and realised Timmy was gone. With their impending move to Arkansas, time was short. There was no way he and Timmy could hitchhike to Ukiah once they had moved.

A daytime escape was impossible with Parnell home in bed. It would have to be at night, while Parnell was working. Steven understood the risks of travelling in the dark, getting into strangers’ cars. But the consequences of being caught by Parnell seemed far worse. He considered confiding in a teacher — but fear held him back. If Parnell was arrested, Steven believed he would be left with no one. He still thought his birth parents didn’t want him.

Steven’s first attempt was one week after Timmy’s abduction. But they didn’t get far before lightning flashed across the sky and rain poured down, forcing Steven to lift Timmy onto his shoulders and return to the cabin cold and wet. Their second attempt, a couple of days later, also failed.

Parnell remained unaware of Steven’s plan. He focused instead on the logistics of moving to Arkansas. Police interest in Timmy’s disappearance was mounting, and they needed to get away. One evening, while Parnell was at work, officers visited the hotel and asked Parnell if any suspicious guests had checked in. He showed them the registry without hesitation. But the mounting pressure made one thing clear: he needed to get Timmy out of there soon.

However, Parnell’s plan did not include Steven.

On February 27th, he began digging a hole behind the cabin — six feet long and three feet deep. It was a grave, meant for Steven and Queenie.

The Escape

On March 1st, 1980, Steven made his third escape attempt. After Parnell left for work, he and Timmy fled into the night. Thankfully, they hadn’t walked far before a Mexican national, Armando Gomez, picked them up and drove them to Ukiah.

The boys arrived around 9 pm. Lost in the dark, they wandered for hours, searching for Timmy’s house. At one point, they passed the Palace Hotel — where Parnell was working his night shift.

Just after 11 pm, they reached the Ukiah Police Department. Steven hesitated, afraid of being recognised and getting Parnell into trouble. He urged Timmy to go in alone, standing back as the 5-year-old pushed open the door and peered inside. But overwhelmed by fear at the sight of a uniformed officer, Timmy bolted back across the car park and into Steven’s arms.

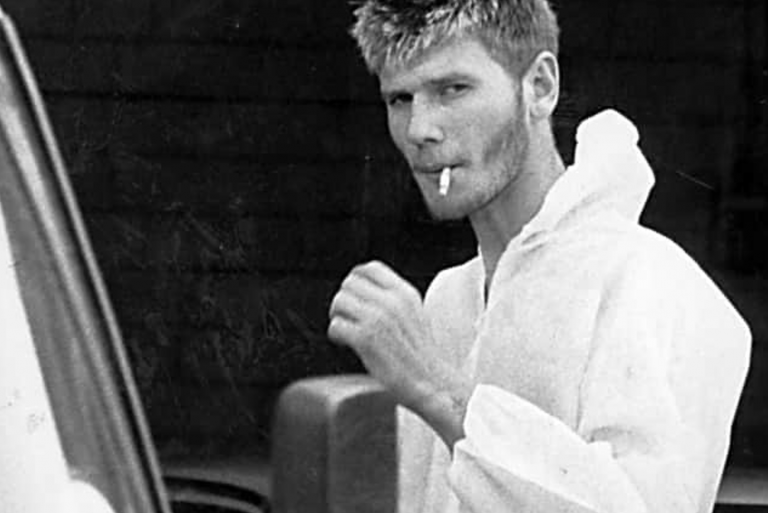

Officer Bob Warner, startled by the fleeting glimpse of a child at the door so late at night, radioed for backup. He chose not to pursue the boys, not wanting to frighten them. Patrol officer Russell VanVoorhis soon located them nearby, and as Warner pulled up, he was stunned to see VanVoorhis cradling Timmy White — the child who’d vanished two weeks earlier. Warner turned to Steven, who revealed his identity. He was taken back to the station for questioning.

Steven was initially terrified he’d be treated as a suspect. He was also still protective of Parnell despite everything and withheld details that would get Parnell into trouble. But with gentle encouragement, Steven eventually disclosed Parnell’s whereabouts. Throughout his questioning, Steven insisted that Parnell had never molested him and had treated him kindly — a heartbreaking indicator of how deeply he’d been groomed.

Shortly before 2 am on the morning of March 2nd, 1980, Kenneth Parnell was arrested. He was taken to the Ukiah Police Station, where Steven, visibly shaken, identified him as his and Timmy’s kidnapper.

Timmy’s mother and stepfather rushed to the station after receiving the news. At first, Angela didn’t recognise her son — his hair was dyed, and he looked dishevelled. She fainted from the shock. When she regained consciousness, she clutched Timmy tightly, sobbing with relief. Through tears, she thanked Steven for bringing her son home. Before returning, Timmy was examined at the local hospital for signs of sexual abuse. Mercifully, none were found.

In the early hours, Steven gave a formal statement to the police. It began:

My name is Steven Stainer [sic]. I am fourteen years of age. I don’t know my true birth date, but I use April 18, 1965. I know my first name is Steven, I’m pretty sure my last name is Stainer [sic], and if I have a middle name, I don’t know it.

Later that day, police searched the cabin in Manchester. Inside, they found Timmy’s Valentine’s Day goody bag and cowboy costume.

Steven was worried about Queenie, so officers escorted him back to the cabin to collect her. Once she was in his arms, he gathered a few belongings and returned to the patrol car. He gave the cabin one last look before turning his back on it — and everything it represented.

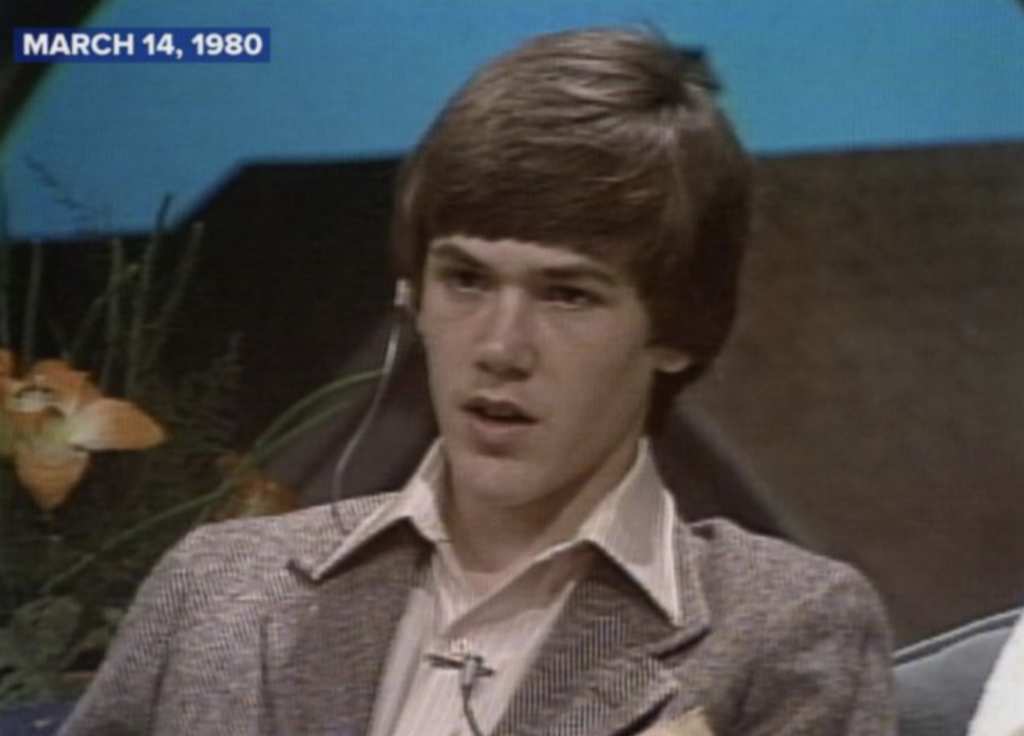

At noon on March 2nd, Steven was taken to a press conference where Timmy sat with his parents. The moment he saw Steven, he sprinted toward him, arms outstretched. As Steven lifted him onto his shoulders, camera flashes erupted across the room, capturing images of the two boys who had saved each other’s lives.

A Hero’s Welcome

After the press conference, Steven began the 240-mile journey back to Merced, where his family and childhood best friend, Sharon, waited. Crowds lined the streets as the police car pulled up to 1655 Bette Street. Camera flashes erupted, and reporters swarmed as Kay and Delbert pushed through the throng, their faces streaked with tears as they embraced their son for the first time since his disappearance seven years earlier.

For Steven, the homecoming was bittersweet. He bathed in clean water, scrubbing away years of grime. He wore new clothes, not the second-hand charity shop cast-offs he was used to. At night, he slept in freshly laundered sheets, a stark contrast to the grimy motels and trailers he’d known for so long.

But emotionally, he was adrift. Adjusting to not being called Dennis proved difficult, and at times, his family struggled to get his attention. Hearing Delbert call him “son” felt alien to him when Parnell had monopolised that word for years. Steven also felt uneasy calling Delbert “Dad”. What Parnell had told him about father-son relationships played heavily on his mind, and he feared his biological father might expect the same twisted intimacy Parnell had demanded. The psychological damage ran deep.

Steven’s relationship with his older brother Cary was equally strained. During Steven’s absence, Cary had spent years wishing on a star that his baby brother would return. Now that wish had come true, but the media frenzy and their parents’ obsession left Cary feeling invisible. Now that Steven was home, he was still getting all their attention.

Steven was questioned again by the police, this time about Ervin Murphy — the second man involved in his abduction. On March 4th, Steven identified him. On March 5th, Murphy was arrested at Yosemite Lodge, where he still worked. The same park manager who, seven years earlier, had refused to display missing posters, now watched as Murphy was led away in handcuffs.

On March 5th, Murphy appeared at Merced County Court and pleaded not guilty to kidnapping. His bail was set at $50,000, which was $30,000 more than the Ukiah court had set for Parnell. He was remanded to Merced County jail pending trial.

The press dubbed Steven a hero for rescuing Timmy. On March 6th, just days after returning home, Steven and his parents travelled to San Francisco to appear on Good Morning America. Steven told the presenter he wasn’t interested in celebrity—he just didn’t want Timmy to suffer like he had.

Later in March, the Stayners learned Steven would receive the $15,000 reward offered during Timmy’s disappearance. The Timmy White Reward Committee had organised a public presentation, and Timmy would hand the money to Steven personally. The ceremony took place in Ukiah on April 6th, Easter weekend, with media cameras capturing the moment an excited Timmy presented Steven with the reward.

After the ceremony, the family extended their trip, travelling in their camper van to retrace Steven’s life with Parnell. He guided them along the route he and Timmy had taken the night they escaped, then to the Palace Hotel, where Parnell had once worked. In Comptche, they visited the place Steven had felt happiest, thanks to the friendships he’d made. He reunited with old friends and his former girlfriend, Lori MacDonald. The next day, they drove out to Mountain View Road to see the cabin where Steven had spent his last nine months with Parnell. Kay and Delbert saw the squalor their son had endured. Behind the cabin, they stood at the edge of the grave Parnell had dug — confronting the horror Steven had narrowly escaped.

On April 14th, following Easter break, Steven enrolled at Merced High School. But the media followed him relentlessly. Reporters walked into the school unchallenged, cornering him in hallways to demand details about the molestation he still denied. Rumours spread quickly, and classmates began accusing Steven of being homosexual.

After just four days, the taunts escalated. One boy hurled homophobic slurs. Steven snapped and punched him in the face, leaving the boy with a black eye and bloody nose. Although the principal sympathised — knowing the boy was a known troublemaker — he suggested Steven take two weeks off to let tensions cool.

Thankfully, his friend Sharon was still in his corner. She organised a pool party, inviting Steven’s friends from before the abduction and classmates she knew would welcome him. For a few hours, Steven could relax, reminded of the friendships he’d left behind in Comptche, and wishing he could see them again.

Steven continued to deny Parnell’s sexual abuse publicly. But shortly after the Ukiah trip, police informed him that the Polaroids of him and the other boy in the shower had been discovered. It turned out that the police hadn’t adequately secured the Manchester cabin, and several reporters had walked through the crime scene, removing evidence. One reporter from the San Francisco Chronicle found the photographs Parnell had taken and handed them over to the Merced police. With the evidence exposed, Steven finally admitted the abuse.

Tragically, however, support was still lacking. His peers bullied him, and his parents dismissed the need for therapy. They insisted the family should handle things privately. His sister Cory later told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch: “He got on with his life…but he was pretty messed up, and he never got any counselling. My dad said he didn’t need any.”

At home, tensions remained. Kay and Delbert struggled to reconcile the seven-year-old they remembered with the teenager before them. Their household rules clashed with the freedom Steven had known, and he began rebelling with alcohol, marijuana, and drugs.

In September 1980, Steven started tenth grade. But school remained a challenge. He’d already missed too much time, and with the trials ahead, he would miss even more. His already difficult homecoming wasn’t getting any easier.

First Trial: Timmy White

The first trial against Kenneth Parnell, for the kidnapping of Timmy White, began in June 1981 in Mendocino County.

Sean Poorman appeared in court to testify against Parnell. He had already faced trial in juvenile court for his role in Timmy’s abduction. Because he cooperated fully with the investigation, his original charge of kidnapping was reduced to false imprisonment, and he was sentenced to two years in a juvenile facility.

Timmy also testified, identifying Sean as the person who had thrown him into Parnell’s car.

Steven took the stand and confirmed that Timmy was the boy Parnell had kidnapped. He also revealed that, prior to Timmy’s abduction, Parnell had asked him to help kidnap other boys.

When Parnell testified, he attempted to shift blame onto Sean Poorman and his stepfather, Henry Mettier Jr. He claimed Mettier was blackmailing him, threatening to harm Parnell’s mother unless he kidnapped a child that could be traded for drugs or money. Parnell insisted he had been at home on the day of Timmy’s abduction, and that Mettier and Poorman had turned up with the boy unexpectedly. However, Timmy testified that Mettier was not his kidnapper.

On June 29th, the jury found Parnell guilty of second-degree kidnapping. He was sentenced on September 25th to seven years, the maximum time that could be given.

Second Trial: Steven Stayner

During the lead-up to Parnell’s trials, Merced police investigated the sexual assaults committed against Steven and several other boys.

However, California’s three-year statute of limitations meant Parnell could only be charged for assaults committed between 1977 and 1980. Typically, this was the period when Steven was maturing, and the assaults against him were decreasing. Even so, Steven still documented 87 assaults during those years.

While gathering evidence, Merced Police visited the schools Steven had attended and interviewed his friends. Some claimed they too had been abused by Parnell. But because the alleged abuse occurred outside Merced County, the police could only pass the information to Mendocino County, which chose not to pursue it.

Ultimately, the Merced District Attorney decided against prosecuting Parnell for any of the documented sexual assaults. Although Steven later testified about the abuse, there was insufficient evidence to support the charges. Even the nude photographs found of Steven and other boys were inadmissible, as they had been circulated by reporters, and it could not be definitively proven that Parnell had taken them.

As a result, Parnell was not charged with the numerous sexual assaults on Steven or any of the other boys. So, when Parnell was extradited to Merced County to appear before the court in December 1981, six months after Timmy’s trial, it was only for the kidnapping of Steven Stayner.

However, the three-year statute of limitations again posed a challenge, although the DA argued that Steven’s kidnapping was ongoing in nature. Thankfully, the court accepted this, and the charges stuck. However, as Parnell had made no ransom demands, he received a reduced charge of second-degree kidnapping.

Parnell’s defence argued that Steven had entered the car willingly and that no force had been used. They claimed Steven had chosen to stay with Parnell because he was unhappy at home, citing the family’s move away from the ranch and the physical discipline he received. Kay and Delbert took the stand and admitted to occasionally punishing their children but denied using excessive force.

Parnell did not testify.

Also standing trial for Steven’s kidnapping was Ervin Murphy. Although there was sufficient evidence to prove his involvement, the statute of limitations applied to him as well.

Murphy testified openly about the events surrounding Steven’s abduction. On the day in question, he had planned to go Christmas shopping in Merced but missed the bus after falling asleep. Parnell woke him up and offered him a lift. After shopping, Parnell drove them to Yosemite Parkway and claimed he was studying to become a minister. He asked Murphy to hand out religious tracts to children walking home from school.

Parnell told Murphy he wanted to adopt an underprivileged child and asked for help in taking one. Murphy, who had been abused as a child himself, believed the plan was well-intentioned.

Outside the Red Ball Gas Station, Murphy followed Parnell’s instructions. His first few attempts to lure children into the car failed. Eventually, they abducted Steven.

Afterwards, Parnell threatened Murphy, warning him that he would be implicated if he spoke to the police. Murphy claimed he tried to call the authorities but lost his nerve when someone answered the phone. Parnell later blackmailed him financially, threatening to report him unless he deposited part of his wages into Parnell’s account. Murphy eventually stopped the payments, and in 1974, Parnell tried to blackmail him again but failed when Murphy slammed the phone down on him.

Murphy said he did not know about the abuse Steven suffered. When arrested, he told police he was relieved Steven was safe.

Barbara Matthias cooperated fully with the investigation. She claimed she had no idea Steven had been kidnapped and was never arrested or charged.

On January 7th, 1982, the jury found both Parnell and Murphy guilty of conspiracy to kidnap and second-degree kidnapping. Sentencing took place on February 3rd.

Under California law, the two convictions – conspiracy to kidnap and second-degree kidnapping – had to be merged, and Parnell received a term of seven years in prison, the maximum that could be given. However, because the kidnappings of Steven and Timmy overlapped, Parnell could not be convicted twice for the same offence. Ultimately, because Parnell had already received seven years for kidnapping Timmy, he was not required to serve the full term and only received an additional twenty months for Steven’s kidnapping.

So once again, Steven did not get the justice he deserved.

Murphy received five years for conspiracy and five years for kidnapping. Again, these terms could not be served consecutively, so his total sentence was five years, though this was longer than the twenty months Parnell received.

Murphy was released on June 21st, 1983, after serving just three years. Parnell was paroled in April 1985 after serving just five years.

In the end, Parnell spent less time behind bars than Steven lost to stolen childhood.

In August 1982, Steven’s case prompted California lawmakers to revise state sentencing laws. The changes allowed courts to impose consecutive prison terms, ensuring offenders served time for each individual offence.

Going Home

Although media attention faded after the trials, the coverage of Steven’s abuse led to renewed harassment at school. He completed his senior year but did not graduate.

When Steven turned 18, he gained access to Timmy’s reward money. Much of it was reportedly spent on drug debts and alcohol. Still, he was able to purchase a small mobile home in Atwater and moved out of the family house. He and Sharon remained close—sharing pizza, watching TV in his trailer, and they even went travelling together.

By 1984, Steven was determined to turn his life around. He had already given up alcohol following a binge that caused internal bleeding and landed him in hospital—a scare that could have been fatal. He spent his spare time working towards his GED and joined a programme visiting kindergartens and primary schools to help prevent child abduction. The idea that he could stop another child from experiencing what he had gave Steven a renewed sense of purpose, and he continued this work for several years.

After most of the money had gone, Steven took a job at a meatpacking plant, where he met Jody Edmondson. They began dating and married a year later, in June 1985. Steven was 20, and Jody was 17. The couple went on to have two children: a daughter, Ashley, and a son, Steven Junior.

Meanwhile, Kenneth Parnell was released from prison in 1985 after serving just five years. When his parole ended in 1987, he was no longer required to report his whereabouts. Steven struggled with the uncertainty, not knowing where Parnell was or whether he was harming other children. He became fiercely protective of his own children, ensuring they were never out alone and always supervised.

In 1988, Steven agreed to work as an advisor on a movie about his life, based on the manuscript of I Know My First Name is Steven by Mike Echols. The title — used for both the book and the film — came from Steven’s written police statement in March 1980, the night he and Timmy arrived at the Ukiah police station.

Steven had been studying for a career in law enforcement, and during filming, he portrayed a police officer escorting the actor playing himself through the crowds as he returned home to Merced. He hoped the movie would raise awareness about child abduction. In an interview with Entertainment Tonight, he said, “Maybe some kid out there that’s missing will see it and come forward and make an attempt to go home.” The movie aired in May 1989.

Sadly, the new life Steven was beginning to build for himself would be tragically cut short.

On September 16th, 1989, Steven finished his shift at a pizza restaurant in Atwater and began the fifteen-minute ride home on his motorbike. It was raining, and the roads were slick. Though Steven was an experienced rider, he was being extra cautious as his helmet had been stolen three days earlier. He was driving below the speed limit when a car suddenly pulled out and stalled in front of him. Steven couldn’t stop in time and collided with the vehicle. The impact threw him forty-five feet from his bike, fracturing his skull. The driver fled the scene.

Other motorists stopped to help as Steven lay by the roadside, drifting in and out of consciousness. He was rushed to Merced County Medical Center but was pronounced dead. He was just 24 years old.

The driver, Antonio Loera, fled to Mexico. He was charged with hit and run and manslaughter, but the manslaughter charge was dropped after investigators found manufacturing faults in his car — a defective carburettor and loose throttle. Loera was sentenced to three months in prison, twelve months’ probation, and ordered to pay $100 to a restitution fund.

The day after Steven’s death, I Know My First Name Is Steven won four Emmy awards.

Steven never knew.

Steven’s funeral was held on September 20th, 1989, at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, which he had joined shortly before his death. Four hundred and fifty people attended. Timmy White, who was now 14, was a pallbearer.

Steven’s sister, Jody, told the congregation:

I’m so glad that he went as Steven Gregory Stayner, our brother.

– Oakland Tribune, 24 September 1989

Steven was laid to rest at Merced County Cemetery. The inscription on his casket read: ‘Going Home.’

Who Was Kenneth Parnell?

Kenneth Eugene Parnell, who stole Steven Stayner’s childhood and shattered the lives of other young boys, was born on September 26th, 1931, in Amarillo, Texas. His early years were shaped by instability. His parents, Cecil and Mary, divorced when he was 5, prompting Mary to relocate with Kenneth and her children from a previous marriage to Bakersfield, California.

Mary was deeply religious, requiring her children to attend the Assembly of God Church three times a week. She instilled a rigid spiritual routine, teaching them scripture at home and insisting on daily prayer.

Parnell’s childhood was marked by frequent episodes of self-harm, beginning after the divorce. In one incident, he extracted four of his own teeth using pliers. At age 8, he shone a torch in his eyes for so long that he required corrective treatment. By 9, he had jumped off a shed roof onto boards embedded with nails, puncturing the soles of his feet. Suicidal ideation became a regular pattern. On one occasion, he removed the safety catch from a loaded .22 pistol and pointed it at his abdomen. His mother witnessed the act.

In 1944, Mary purchased a boarding house. The following year, when Kenneth was 13, one of the boarders groomed him into performing a sexual act. Soon afterwards, he set fire to a pasture and was sent to Bakersfield Juvenile Hall under the recommendation of a psychiatrist, who hoped confinement might address what was then labelled his “perversion.”

Shortly after his release, Parnell stole a car and was sent to a juvenile facility, where he remained until February 1947. According to reports, while there, he participated in sexual activity with other male inmates. By December 1947, now 16, he was arrested for engaging in public sex acts with men.

His criminal behaviour escalated. Within months, he stole another vehicle and was incarcerated at the Lancaster facility in California. After escaping and returning to Bakersfield, he developed an infatuation with a young boy and was re-arrested and sent to Kern County Jail. During this period, Parnell attempted suicide by drinking disinfectant. He was subsequently committed to a mental hospital in Napa for 90 days, but escaped again, intent on returning to the boy in Bakersfield — stealing another car in the process. He was rearrested and transferred back to Lancaster.

In May 1949, Parnell was released and moved back in with his mother. Later that year, he married 15-year-old Patsy Dorton. But he was far from settled.

In March 1951, 19-year-old Kenneth Parnell purchased a fake deputy sheriff’s badge and used it to impersonate a police officer. He approached 9-year-old Bobby Green, who was playing with friends outside Bakersfield, and told Bobby he matched the description of an escaped juvenile offender. Parnell said he needed to take him in for questioning.

Instead, he drove the terrified boy to a remote stretch of Kern River Canyon and sexually assaulted him.

Parnell was arrested six days later. At a preliminary hearing held that same day, he confessed to sodomising Bobby and forcing him to perform oral sex. He also confessed to thinking about strangling Bobby to prevent him from telling anyone what Parnell had done. But instead, Parnell drove Bobby back to the place he had been taken from.

Parnell was held at Kern County Jail until April 20th, when he pleaded guilty to the charge of lewd and lascivious contact on and with the body, members, and private parts of a male child under the age of fourteen. The judge ordered three separate psychiatric evaluations.

On May 11th, the court reviewed the findings. Parnell was declared a sexual psychopath and recommended for treatment in a state mental hospital. He was sent to Norwalk State Hospital for further evaluation, where he was diagnosed as a sexual psychopath without psychosis and deemed legally sane.

At a hearing on June 22nd, the judge ordered Parnell to be committed to Norwalk indefinitely, until he was considered fit for release.

Shockingly, when police investigated Steven Stayner’s disappearance decades later, they requested a list of known child molesters in Merced and surrounding counties. Despite his conviction for assaulting Bobby Green, Parnell had never been registered, and his name wasn’t on the list.

During this period, his wife Patsy gave birth to their daughter. One psychiatrist noted that Parnell seemed excited about the birth and was asking about treatment options. In June, he wrote to the judge complaining about the lack of therapeutic support at Norwalk and requested to be released back to Bakersfield for outpatient care and supervision.

Whether this was a genuine attempt to seek help or a calculated move to manipulate the court remains unclear. But on September 11th, 1951, Parnell took matters into his own hands, and he sawed through a window lock and escaped. He was recaptured a few weeks later and placed in the hospital’s maximum-security ward.

Then, on October 14th, he escaped again. This time, he remained at large for four months before being caught in New Mexico in February 1952. Although the judge attempted to have him readmitted to Norwalk, Parnell was ultimately sent to San Quentin’s maximum-security prison, where he served just over three years.

Notably, during both escapes, he made no attempt to visit his daughter. Furthermore, decades later, in a 2000 interview, Parnell offered a chilling glimpse into his psyche. He claimed he had molested Bobby Green because his pregnant wife couldn’t satisfy him, and he needed another outlet. The remark underscored a disturbing truth: his family had never truly mattered to him. They were props in a narrative that served his own desires.

Parnell was paroled in April 1955 on the condition that he receive ongoing psychiatric treatment—a requirement he failed to meet. He returned to Bakersfield, visited his mother, and took a job that violated his parole terms. At a hearing in September 1956, he was sentenced to three months at Folsom State Prison. He was paroled again on December 17th and returned to Bakersfield.

Parnell and Patsy divorced in 1957. That August, he married Emma Schaffer, ten years his senior. They had a daughter together, but Emma divorced him in 1961. Parnell later claimed to have married a third time in 1968, though no records of that marriage or divorce exist.

In 1960, he moved to Utah. Desperate for money, he used a revolver to hold up a service station in Salt Lake City. In 1961, he was convicted of armed robbery and grand larceny. He was released in September 1967 under the condition that he never return to Utah.

For the next few years, Parnell drifted from job to job until May 1972, when the Curry Company hired him as a night auditor at Yosemite Lodge. Parnell had lied on his application about his criminal past and mental health history, and Yosemite National Park was a good place to lay low. It was there that Parnell met 30-year-old Murphy.

Ervin Edward Murphy was born on July 11th, 1941, in South Dakota. Murphy’s mother was abusive, and he remembers her beating him with a strap when he was 3. Soon after this incident, his mother deserted the family, leaving his father to raise him and his nine siblings. When Murphy was 16, he dropped out of school and left home. He drifted around California doing menial work until the mid-1960s when he joined the Job Corps and learned kitchen work. But he was kicked out of the Job Corps after he was racially abusive towards a Black trainee. Murphy then resumed drifting until 1969, when the Curry Company hired him.

Murphy was described by many of his colleagues as a likeable character. He was the lonesome type, but would do anything for anyone else. He liked people and wanted to be liked in return. Murphy hadn’t planned to stay long at Yosemite, but felt he had found friends there.

Murphy was easily influenced by others and tended to believe everything he was told, and it is easy to see how someone like Parnell could manipulate Murphy into helping him abduct a child. And so in December 1972, Parnell and Murphy kidnapped 7-year-old Steven Stayner as he was walking home from school in Merced.

In retracing the years between Steven’s abduction and Parnell’s final arrest, a disturbing pattern emerges — not only of evasion, but of a man who slipped repeatedly through cracks in the justice system.

In April 1985, Parnell was released on parole due to good behaviour after serving just five years for the kidnappings of both Timmy and Steven. His two-year parole stipulated that he wasn’t allowed to leave Alameda County, he was not allowed in the company of children, and he had to attend regular counselling sessions. His parole officers checked on him up to six times per week at the boarding house in Berkeley City, where he had been assigned. The public was outraged that a convicted child kidnapper was now walking among them.

After completing his parole in 1987, Parnell got a job as a volunteer caretaker in a boy’s home in Oakland, California — an unsettling placement given his history as a convicted kidnapper and sexual sadist. His criminal history had gone unchecked. After the movie I Know My First Name Is Steven aired in May 1989, Parnell’s identity was uncovered, and he was fired from his job.

Parnell’s mother described him as honest, saying he loved children and animals and would never harm anyone. She said that Parnell had visited her many times, and he never had a child with him. However, it is worth noting that during the case against him for assaulting Bobby Green in 1951, Mary was the one who hired an attorney for her son, so she knew exactly what he was capable of.

In December 2002, the police received a tip-off that Parnell was attempting to abduct another young boy. The 71-year-old was in poor health and received 24-hour-a-day nursing care at his Berkeley apartment. He had suffered a stroke and had several ailments, including emphysema and diabetes.

The tip-off had come from Diane Stevens, his caregiver’s sister. He had offered Diane $500 to procure an English-speaking Black boy between 4 and 6 years old, along with a birth certificate — presumably aware from his experience kidnapping Steven that documentation was vital in concealing the child’s true identity.

Diane was aware of Parnell’s past and feared he would approach someone else if she refused. With that concern in mind, she pretended to accept his offer, then immediately alerted the police and collaborated with them to carry out a sting operation.

On January 3rd, 2003, Diane told Parnell that she had found him a boy. She arranged to first drop off the birth certificate at his apartment in return for $100. She would then collect the boy from her car and return with him in exchange for the remaining $400. Diane wore a wire as she entered Parnell’s apartment to deliver the birth certificate. Moments later, the police entered and found the $400 laid out, ready to complete the transaction.

Parnell was arrested. A search of his apartment revealed children’s clothing, books, videos, and toys, along with pornography, condoms, and sexual aids.

In a jailhouse interview, Parnell claimed his motive was innocent, and he wanted to raise the boy like any child. However, at his trial on February 2nd, 2004, Diane testified that Parnell requested the child have a clean rectum, clearly indicating sexual intent.

Timmy White and Sean Poorman both testified against Parnell at the trial, and a transcript of Steven’s 1981 testimony was read to the jurors.

Although there was no actual child in the case, there was enough evidence to prove the charges against Parnell of solicitation to commit a felony, trying to buy a human being, and attempted child stealing. He was convicted on February 9th, 2004, and was sentenced to twenty-five years to life under California’s three-strikes law.

At the trial, Timmy hugged Sean Poorman, forgiving him for his part in his kidnapping.

On January 21st, 2008, 76-year-old Kenneth Parnell died of natural causes while incarcerated at the California Medical Facility in Vacaville, California. He had served less than four years of his sentence.

Aftermath

Ten years after Steven’s death, the city of Merced invited residents to propose names for city parks honouring notable citizens. Steven’s family requested that one be named Stayner Park — a tribute to Steven and a call to raise awareness for missing children. The proposal was rejected, as the Stayner name was also associated with Steven’s brother, Cary, who later murdered four women. (Read about Cary’s case here.)

In 2010, after lengthy discussions, a monument of Steven holding Timmy’s hand and leading him to safety was unveiled in Merced’s Applegate Park. It stands as a monument to Steven’s bravery and a message of hope to families of other missing and kidnapped children.

But one person was heartbreakingly absent from the unveiling. On April 1st, 2010, the same year the statue was erected, Timmy White passed away from a pulmonary embolism. He was just 35 years old.

Timmy had served as a deputy in the LA County Sheriff’s Department and was married with two children. In the years before his death, he gave school talks about stranger danger and child abduction. By following in the footsteps of the teen hero who once rescued him from a prolific paedophile, Timmy became a beacon of hope himself — shining light on the enduring dangers of child abduction.

Sources

Books

From Victim to Hero: The Untold Story of Steven Stayner. Jim Laughter. 2010. Buoy Up Press.

I Know My First Name is Steven. Mike Echols. 1999. Pinnacle Press.

Court Documents

Parnell v Superior Court (People) (1981) Civ. No. 50913. Court of Appeals of California, First Appellate District, Division Two. May 21, 1981.

People v. Parnell California Court of Appeal. June 28, 2006.

Newspaper Articles

Californian (Salinas) – Parnell Sex Charges Dropped. Volume 109, Number 94. April 18, 1980. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Daily Kent Stater – Kidnapping Suspect Freed on Bail. March 6, 1980. Via Daily Kent Stater Digital Archive.

Desert Sun – Boy’s Kidnapper Sentenced. Number 46. September 26, 1981. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Evening News – Mystery Woman Meets Stayner’s Real Parents. March 19, 1980. Via Google Books.

Hanford Sentinel – Kenneth Parnell Convicted of Trying to Buy Little Boy. February 10, 2004. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Hanford Sentinel – Man Who Kidnapped Steven Stayner Goes on Trial in Child-Buying Case. February 3, 2004. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Hanford Sentinel – Parnell Gets 25 Years to Life for Trying to Buy Little Boy. April 16, 2004. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Hanford Sentinel – Stayner: Life With Kidnap Suspect. Volume 1981, Number 296. December 16, 1981. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Lodi News-Sentinel – Missing Boy’s Saga Continues. March 4, 1980. Via Google News.

Los Angeles Times. Second Man Seized as Kidnapping Suspect. March 5, 1980. Via Newspapers.com.

Napa Valley Register – Convicted Child Kidnapper Arrested. Volume 140, Number 150. January 5, 2003. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Napa Valley Register. Hunt for Child Called Off. Volume 111, Number 105. December 13, 1972. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Napa Valley Register – Mendocino County Doesn’t Want Parnell. Volume 125, Number 186. April 5, 1988. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Napa Valley Register. Reward Upped. Volume 111, Number 236. May 15, 1973. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Napa Valley Register – Stayner Kidnapper Having Hard Time Finding a Job. Volume 127, Number 129. January 9, 1990. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Petaluma Argus Courier – 2 Kidnapped Boys Hitchike to Freedom. Volume 144, Number 169. March 3, 1980. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat – A Long Road to Trial. Volume 124, Number 97. February 15, 1981. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat. Assembly Passes Kidnap Law. Volume 125, Number 259. August 26, 1982. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat – Kidnap Accomplice Released. Volume 126, Number 191. June 2, 1983. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat – A Swift Conviction of Parnell. Volume 124, Number 211. June 30, 1981. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat – Kidnap Case Has Happy Ending. Volume 123, Number 115. March 3, 1980. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat – Kidnap Suspect’s Troubled Past. Volume 123, Number 116. March 4, 1980. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat. Man sentenced to 3 Months in Jail in Stayner Hit-Run Death. Volume 133, Number 76. January 5, 1990. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat – Massive Search for Ukiah Youth. Volume 123, Number 102. February 17, 1980. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat – Parnell Blames Hank for White Kidnap. Volume 124, Number 207. June 25, 1981. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat. Parnell Freed in Bay Area. Volume 128, Number 190. April 5, 1985. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press Democrat – Parnell Sentenced – 20 Years. Volume 125, Number 86. February 4, 1982. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press-Tribune (Roseville) – Driver sought in Stayner Accident. Volume 85, Number 66. September 18, 1989. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Press-Tribune (Roseville). Family Remembers Former Kidnap Victim as Survivor. Volume 85, Number 69. September 21, 1989. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

San Bernardino Sun – Kidnap Victim Stayner Dead at 24. Volume 116, Number 260. September 17, 1989. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

San Bernardino Sun – Police Say Stayner Kidnapping Case Pretty Well Wrapped Up. March 21, 1980. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Santa Cruz Sentinel – State Claims Sex Behind Kidnapping. Volume 125, Number 58. March 11, 1981. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Santa Cruz Sentinel – Kenneth Parnell’s Lonely Odyssey. Volume 124, Number 54. March 5, 1980

Tulare Advance Register. Kidnap Mystery Woman Flees. Volume 98, Number 77, 20 March 1980. Via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

TV / Movies / Videos

20/20 Evil In Eden, Pt 1: Two Brothers Tied to Yosemite, One a Hero, The Other a Monster. ABC News.

20/20 Evil In Eden, Pt 2: Steven Stayner’s Abduction Changes Family’s Life Forever. ABC News.

20/20 Evil In Eden, Pt 3: Steven Stayner Escapes Captor, Returns Home After Seven Years. ABC News.

20/20 Evil in Eden, Pt 4: Cary Stayner Takes Refuge in Yosemite. ABC News.

Captive Audience: A Real American Horror Story. First episode date: April 21, 2022 (USA). Hulu.

Entertainment Tonight Report On I Know my Name is Steven. April 20, 1989.

Good Morning America Interview. March 14, 1980.

I Know My First Name is Steven. First episode date: May 22, 1989 (USA). NBC.

Websites

Cinemaholic – How Did Steven Stayner’s Dad Del Stayner Die? April 22, 2022

CNN – Steven Kidnapper Convicted. February 9, 2004.

Crime And Investigation – Going Home: The Story of Steven Stayner.

East Bay Express – Inside the Monster. January 15, 2003.

ENews – Steven Stayner’s Kidnapping, Cary Stayner’s Horrific Crimes and One Family’s Unbelievable Story. April 21, 2022.

Facebook – Steven Stayner: A True Hero.

Guardian – There Was A Lot Of Torment: The Family Who Endured Two True Crime Stories. April 20, 2022.

Imgur – 45 Years Ago Today Steven Stayner Went Missing.

Independent – Two Kidnapped Boys, a Hero’s Return, Then a Tragic Twist: The Unbelievable Story Of Steven Stayner. April 28, 2022.

Jim Laughter – From Victim to Hero.

Los Angeles Times – Man Gets 90 Days in Death Of Stayner. January 5, 1990.

Los Angeles Times – Who Was Steven?: The Little Boy Who Had Been Kidnaped Never Found Himself. September 22, 1989.

New York Post – Captive Audience Revisits 1972 Steven Stayner Kidnapping and His Tragic End. April 21, 2022.

Press Democrat – 24 Years After Ukiah Abduction, White Again Faces Parnell. February 5, 2004.

Santa Cruz Sentinel – Steven’s Other Mother. March 20, 1980

Seattle Times – A Child Abductee’s Journey Back. January 20, 2007.

SF Gate – Child Predator Sentenced to 25 Years to Life / Steven Stayner’s Kidnapper Tried to Buy 4-year-old in Berkeley. April 16, 2004.

SF Gate – Sex Predator Tried to Buy Son ‘To Raise’ / He ‘Just Wanted to be Loved,’ Parnell Says from Jailhouse. January 9, 2003.

SF Gate – Heroism, Tragedy and Cold-Blooded Murder: The Stayner Brothers. January 23, 2019.

Washington Post – Man Pleads Innocent in Calif. Kidnapping of Boy, 5. March 5, 1980.